Cabinet of curiosities

Introduction & Index

Here is a cabinet that is becoming filled with architectural curiosities. There have been recent cabinets of Philosophical Curiosities (by Roy Sorensen) and Mathematical Curiosities (by Ian Stewart), but not, so far, an architectural cabinet. I hope to rectify this situation. I plan to include some simple mathematics and more than one philosopher.

Renaissance air conditioning

Hero of Alexandria, the engineer and natural philosopher, lived in the first century AD and worked in that city’s celebrated Library and Museum. His best-known book is the Pneumatics, which might sound like a physics textbook, but is in fact a compendium of surprising devices, tricks and toys, some of which operate automatically once they are set going.

Acanthus leaves in a basket

The three principal ‘orders’ of classical architecture – Doric, Ionic and Corinthian - are readily distinguished by the capitals on their columns. Of these, the Corinthian capital is the most elaborately decorated. There are many variants, but the basic form is that of a cylindrical basket with an acanthus plant growing through the basketwork.

"Life is always right: it is the architect who is wrong"

Henry Frugès was a French industrialist who owned a sawmill and a sugar refinery in Bordeaux, and imported goods from the French colonies. In 1923 he read an article by Le Corbusier in the journal Esprit Nouveau and went to Paris to look up the author. Corbusier was then little known, but Frugès was impressed by his sympathique manner, his heavy black spectacles, and his ideas about the industrial production of houses in quantity.

The House of the Faraway Heart

Harold C Price founded a company in Bartlesville, Oklahoma that built oil and gas pipelines all over the world. On the recommendation of Bruce Goff, then Dean of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma, Price commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright in 1952 to design a high-rise office building for the firm.

Schinkel's panorama

Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Germany’s greatest neo-classical architect, trained for the profession at the start of the 19th century, and toured France and Italy studying buildings and making drawings. He came back to Berlin in 1805, but the following year Napoleon defeated the Prussians, the French occupied the city, and all construction work came to a halt. Schinkel turned to painting, by which he made his living for the next ten years.

Cathedrals for airships

Some of the world’s largest buildings by volume are used for the construction and shelter of aircraft and spacecraft. The biggest of all is the Boeing Everett Factory in Washington State, originally used for making the company’s 747 airliner. Only slightly further down the list are several hangars remaining from the programmes to develop airships in the USA, Germany and Britain in the early 20th century.

The Great Workroom on the dining table

S C Johnson & Son, Inc of Racine Wisconsin produce domestic cleaning products, of which the best-known is Johnson’s Wax. In the mid-1930s the president Herbert ‘Hib’ Johnson commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design a headquarters for the company with offices and research laboratories.

Writing on the ground

Artists and illustrators have been fascinated by resemblances between the forms of buildings and the shapes of letters, and have made images of alphabetical buildings.

The Arch of Constantine in a French garden

In France in the mid-17th century there was a fashion for installing large illusionistic paintings in gardens. These were positioned, and their perspectives carefully calculated, so as to give the impression that the spaces of the gardens continued beyond their actual boundaries.

The black glass skyscraper: a really bad idea

The first large buildings to have walls (and roofs) made completely of glass were the great horticultural greenhouses of the early 19th century. The most magnificent glasshouse of all was of course the gardener Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of 1851, a conservatory for artefacts collected from across the world. In America at the same time the engineer James Bogardus was pioneering factory and warehouse buildings with iron structural frames and large areas of glazing. Contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic were impressed with how speedily such buildings could be erected from their prefabricated parts.

Rocking the stones up the pyramids

A collection of architectural curiosities could not be complete without some mention of the Secrets of the Pyramids. This is not the place for the wilder speculations of Pyramidology: that they were temples of initiation into the Egyptian Mysteries, beacons for guiding alien spaceships, accumulators of cosmic energy… There are mysteries enough in the practical question of how these gigantic monuments were constructed.

Bellotto and bomb damage

Bernardo Bellotto was the nephew and pupil of Antonio Canaletto. Bellotto painted many of the exact same subjects as Canaletto, and together they produced finished drawings and engravings whose authorship is not always easy to assign.

Roger Rabbit and the Red Cars

The movie ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’ is set in Los Angeles in 1947. The wicked Judge Doom has bought Toontown – which is Hollywood of course – and is planning to demolish it. In a key sequence, Doom confronts Roger and shows him a terrifying vehicle whose tanks are filled with a liquid that the characters refer to in horror as ‘dip’. This is acetone, which dissolves celluloid, and is therefore fatal to Toons.

City of Darkness

What would happen if a city was built without any of the benefits of planning, architectural design, or building control? The experiment was tried, in Hong Kong, from the 1950s to the late 1980s. In 1898 the British took over the New Territories on the opposite side of the harbour from Hong Kong Island. The Chinese however ensured that the Walled City of Kowloon, an ancient fortress within the Territories covering 2.6 hectares of land (about four football pitches), remained in their hands.

Architectural models at a scale of 1:1

Buildings are large and expensive. Many of them are one-offs, and the design is not repeated. Architects have traditionally used physical models of wood or plaster to make predictions, for themselves and clients, of what their schemes will look like once built. Usually these models are reduced in scale, to be of manageable size and relatively cheap to construct (although important sculptural and decorative details may be modelled at actual size).

Greek temples made of wood

In vernacular architecture, and in the craft tradition, inherited designs are copied and copied again. Builders and craftspeople use routine methods learned in their apprenticeship, and take existing buildings, weapons and tools as models. In this extended process of repeated copying, small changes can creep in, and the design undergoes a kind of evolution.

Lessons in the snow, lessons on the beach

Norman Collier was a pupil at Aspen House School, Lambeth, in London in the 1930s. He remembers how, in the winter “… when we got there in the morning, the snow would have blown in on to the tables and chairs and we would have to clear it off before we could start.” The snow could get in because the classrooms were freestanding pavilions with large unglazed openings in place of windows. Aspen House was an ‘open-air school’: part of an international movement in education in the first half of the 20th century.

Boy (and girl) architects and their toy buildings, Part 2

Wooden or stone toy building blocks are piled up under gravity, each block resting on those below – like the pyramids. The precariousness of towers, bridges and overhangs is all part of the fun. The Lilienthals argued that their stones gave greater structural stability than wooden blocks, because of their greater weight and rougher surfaces. Even so, the Art Department of the Anker company resorted to using glue in the construction of their largest and most complex display models.

Boy architects and their toy buildings, Part 1

Plato said that “if a boy is to be… a good builder, he should play at building toy houses… and be provided by his tutor with miniature tools modelled on real ones.” From the late 18th century we can follow this learning process in action. Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Maria Edgeworth in their book Practical Education of 1798 recommended that the nursery be equipped with “pieces of wood of various shapes and sizes, which [infants] may build up and pull down”, and that older children might make ‘models of architecture’ from cardboard and glue.

London in a Japanese atlas: by Miho Nakagawa

Surprisingly, maps are cultural products. Each country has its own cartographic style reflecting perceptions of cities, their systems and written languages. When tourists visit a country for the first time, they are sometimes bewildered by the different conventions operating there.

Thomas Edison pours whole houses from concrete

Historians of construction focus on Europe as the place where houses built of concrete were pioneered at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. But over in West Orange, New Jersey, Thomas Edison was dreaming in his laboratory of an entire concrete house made in a single operation, including not just walls and floors, but the foundations, the roof, the staircase, chimneys, mantelpieces, even ceiling decorations.

Sacred polygons

The architectural historian Rudolf Wittkower describes the centrally-planned church as ‘the climax of Renaissance architecture’. Leon Battista Alberti in his book On the Art of Building (1452) lists a series of regular polygons as suitable for the plans of ‘temples’: the square, the hexagon, the octagon, the decagon (ten sides), and the dodecagon (twelve sides).

Josephine Baker captivates the Modernists

On 2nd October 1925 the ‘Revue Nègre’ opened in the Théâtre du Champs-Élysées in Paris. The critic Pierre de Régnier describes the first entrance of the show’s star, the American dancer and singer Josephine Baker.

Clonehenge

Of all the world’s great architectural monuments, which has most often been reproduced in three-dimensional facsimile? A fair guess is that it would be Stonehenge. Nancy Wisser’s wonderful Clonehenge blog gives photographs and descriptions (in 2020) of 97 permanent full-size replicas in many countries, of varying degrees of accuracy, plus a much larger number of temporary versions and scaled-down copies. More are being manufactured all the time.

"Sparrowhawks, Ma'am"

When the Crystal Palace was built in Hyde Park in 1851, it enclosed a number of mature elm trees. It also enclosed the resident population of sparrows, whose presence was not wanted, flying among the precious and delicate exhibits. Shooting them was clearly out of the question. As in all great matters of state, Queen Victoria consulted the Duke of Wellington. His reply was brief: “Sparrowhawks, ma’am”. And that proved to be the solution

Quarter-detached

The familiar names for house types distinguish the ways in which they are attached - or not - to neighbouring houses: detached, semi-detached (in pairs), terraced (in rows). But there is another possible configuration that is found only rarely, and for that reason has no standard designation, where houses are grouped together in fours. We might call these ‘quarter-detached’.

Beach holidays for Nazis

There was a time when the completion of ‘the world’s tallest building’ was an occasion for great public excitement and national pride. This is hardly true any more. Do you even know which building carries the title today? (In 2020 it is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, completed in 2010, which at 828 metres is more than twice the height of the Empire State.) The rivalry between tall buildings has become a kind of pathology to be understood through the teachings of Sigmund Freud. Perhaps a more curious question is ‘what is the world’s longest building?’ – although, since this is not the subject of competition, few people know the answer either.

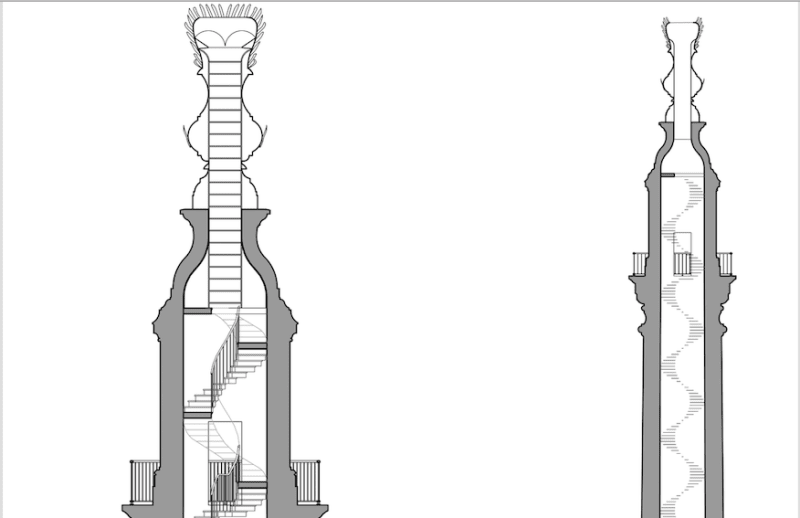

The Architecture Pill: by Eva Branscome

In 1967 the Austrian architect Hans Hollein stuck a glazed green pill to a sheet of A5 stock paper and typed his name and the year below, adding to this the word Architektur and his handwritten signature.

Painting the laundry boats: by Murray Fraser

A guest article from Murray Fraser, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London

Venice, Venice, Venice, Venice, Venice...

In the late 19th century patients with respiratory diseases moved to parts of rural California now built over by Los Angeles for the sake of their health - surprising as it might seem today - to benefit from the pure air and sunshine. Abbot Kinney, an asthma sufferer, spent a night in 1880 at the Sierra Madre Villa Hotel and had the best night’s sleep of his life - even though he arrived without a reservation and had to sleep on the hotel’s billiard table. He decided to move to California and, with a fortune made in the tobacco business, embarked on a series of development projects, culminating in the foundation of a seaside resort which he named Venice Beach. This was an independent city until 1926, when it was absorbed into LA.

Architects in fiction, Part 2

Pecksniff in Martin Chuzzlewit builds nothing; Otto Silenus in Decline and Fall is contemptuous of the occupants; the characters of Howard Roark and Peter Keating in The Fountainhead are flawed in their different ways; and Kem Roomhaus’s buildings fail technically. An extreme point is reached with Anthony Royal, who presides over the complete social and physical disintegration of his major architectural work.

Architects in fiction, Part 1

Women’s magazines of the post-World War II years published romantic short stories in which the heroine’s dream was to marry an architect: a man with an artistic side who nevertheless could bring in a regular salary. The Goodreads website listed 59 ‘romance fiction’ novels in print in 2019 with architects as leading characters. The profession has not been treated so kindly in the literary novel.

Sigmund Freud and the Monument: by Ro Spankie

In 1909 Sigmund Freud gave a lecture in America on psychoanalysis, in which he said that the Monument to the Great Fire of 1666 in London was a 'mnemonic symbol' that resembled a hysterical symptom.

Christopher Wren and friends watch the bees

The 17th century natural philosopher Samuel Hartlib wrote a book called The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees, in which he described a beehive with glass windows through which the apiarist could watch the occupants. The drawing of the hive was made by the young Christopher Wren, not yet an architect.

Noon on the church floor

In the 16th and 17th centuries, churches were turned into giant camera obscuras, The sun entered a small hole in the roof, and cast a bright image at noon onto a line running north-south on the floor. The purpose was to determine the date of Easter.

Turning consumptives to the sun

In Europe in the 19th century tuberculosis – or consumption as it was known – was the cause of one death in four. There was no pharmaceutical cure, and the only palliative treatment was to remove patients to places where the air was clean and dry, and to expose them to ‘heliotherapy’ or the restorative powers of sunshine.

Operation Teapot

In 1955 the US Department of Defense erected a number of buildings in the Nevada desert and exposed them to a nuclear explosion. The project was known as Operation Teapot. The purpose was of course to gather data for making predictions of the effects of weapons dropped on cities in some future nuclear war.

Listing buildings

The Tower in Pisa leans by accident. There have however been a few houses built deliberately at angles: as though the entire structure had been designed with vertical walls and flat floors, and had then been tipped over. On entering, the visitor experiences strange sensations.

The spandrels of San Marco (or rather, the pendentives)

In 1979 an intense controversy in the theory of natural evolution was provoked by a paper, 'The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm', by the biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin

Salt in the cellar

The pumping of brine from below the town of Northwich in Cheshire in the 1870s created large unsupported caverns that collapsed with little warning, into which buildings fell.

Willis Carrier's epiphany in the fog

The American engineer is inspired to invent 'dew point control' for air conditioning, while standing in the fog on Pittsburgh railroad station in 1902.

The Squaring of Circleville

The geometrical conundrum of squaring the circle goes back to the ancient Greek mathematician Anaxagoras, and perhaps to Babylonian scholars before him. Given a circle, is it possible to construct a square of the exact same area, using only compasses and a straight edge? Many hopeful geometers, including Leonardo Da Vinci, battered their heads against the problem, until it was finally proved insoluble in 1882. But the inhabitants of a small town in Ohio had actually achieved the impossible some decades earlier.

Cool black and warm white

The American engineer Harold Hay designed houses in the 1960s and 70s that were cooled, not using mechanical ventilation or air conditioning, but by natural means. The houses were sited in parts of the United States with clear skies at night like California and Arizona. They had bags or tanks of water on the roof that were warmed during the day, and radiated their heat back to the blackness of the sky during the night. This created the cooling. Hay called them Sky-Therm houses. In desert regions the effect has been used for centuries to make ice at night.

The world's tallest buildings as harbingers of economic doom

While a country's tallest building is under construction, its economy falls into recession.

Jeremy Bentham watches the chickens

Jeremy Bentham, the 18th century Utilitarian philosopher and penal law reformer, is famous in architectural history for his invention of the Panopticon: a design of prison in which the cells were to surround the ‘inspector’ in a circle, so that all the inmates could be continually watched from the centre. (In fact, Jeremy was *not *the inventor. He was always punctilious in giving the credit to his engineer brother Samuel.) Jeremy sketched a frontispiece for his book on the Panopticon: the oval figure is a schematic plan of the ring of cells. It also, appropriately, resembles an eye. The accompanying text from Psalm 139 reads: “Thou art about my path and about my bed: and spiest out all my ways.”

Edwin Lutyens draws for a blind architect

In his biography of Edwin Lutyens, Christopher Hussey recounts an episode in the architect’s life “which he described as ‘a great personal adventure’ and as having taught him a lesson never forgotten.” Lutyens spoke of this in an address to the Cambridge Architectural Society on November 8th 1932:

Ornament and criminology

In 1910 Adolf Loos gave a lecture in Vienna that was prophetic for modern architecture in Europe. The title was ‘Ornament and crime’. Loos announced a great discovery that he was passing on to the world: “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.”

Of Alley

In the 17th century George Villiers Duke of Buckingham owned York House in London, which stood on land between The Strand and the River Thames. The Duke disposed of the property in 1672 to a developer, Nicholas Barbon, on condition that the new streets be named after himself: George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street and Buckingham Street. Adjoining Buckingham Street, Barbon made a narrow lane called Of Alley. John Roque’s map of London of 1746 shows the plan.