Anamorphosis in a painting by Vermeer

This piece was written for a volume celebrating the life and work of John Sharp, mathematician, educator, and inventor of mathematical recreations: Sharp Forms: Life at the Edge of Art and Mathematics (Tarquin: https://www.tarquingroup.com/sharp-forms-life-at-the-edge-of-art-and-mathematics.html). John was particularly fascinated by anamorphic images.

Vermeer’s painting ‘Woman Standing at a Virginals’ is in the collection of the National Gallery in London. The woman looks directly at us, her fingers on the keyboard of the instrument. Beyond her on the back wall hang two ‘painted paintings’. One shows a Cupid holding up a playing card, an ace of hearts. This is traditionally taken to signify fidelity to one alone, suggesting that Vermeer’s larger theme here is sacred love, in contrast with the pendant, ‘Woman Seated at a Virginals’, who represents profane love[1].

The second ‘painted painting’ behind the standing woman is a landscape. The Vermeer scholar Gregor Weber has recognised this as a copy of a real picture by a Delft landscape artist Pieter Groenewegen, a friend of Vermeer’s father[2]. It is possible that the picture belonged to, or passed through the hands of the Vermeers, father and son, who both dealt in paintings. Vermeer reproduces only a slice at the right-hand side of Groenewegen’s composition, which is a wider panorama. He omits the rising ground and trees at the left.

The open lid of the virginals is decorated with a third ‘painted painting’, another landscape. In my book Vermeer’s Camera I describe how I was able to reconstruct the three-dimensional geometry of the room shown in this and ten other interiors by Vermeer[3]. I used a process of reverse perspective, in effect working the normal operation of perspective construction backwards. As part of this process I reconstructed the virginals in both the ‘Woman Standing’ and the ‘Woman Seated’. The two instruments are very similar in their dimensions, the design of their legs, and the painted marbling on the cases. It seems likely that Vermeer has painted the same instrument twice. But he has given the two versions different landscapes on the lids. The picture in the ‘Woman Seated’ is much darker: a view of a river bank with trees and figures, whose original has not been identified. The lid in the ‘Woman Standing’ however features a second version of the Groenewegen. This time the whole panorama is copied.

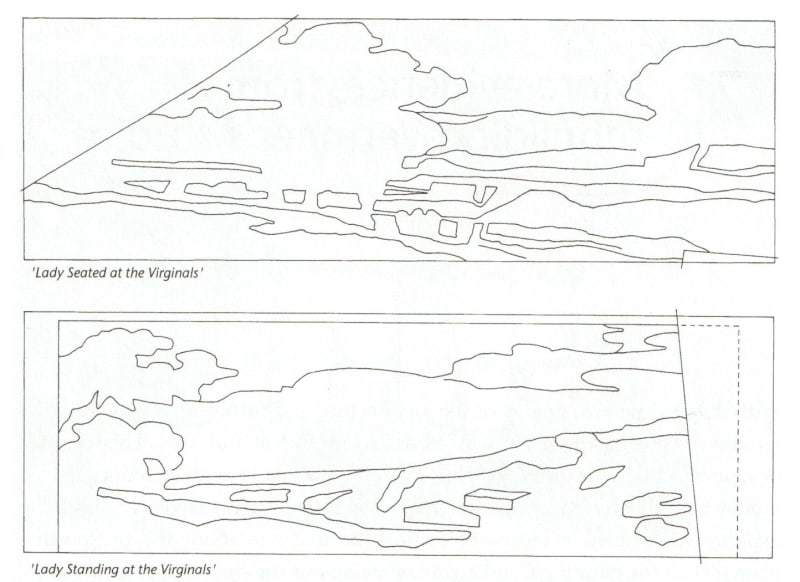

Reconstructing what these two landscapes would have looked like frontally, I discovered that they would have been unnaturally elongated. They look normal when seen at very oblique angles in Vermeer’s renderings: but they are ‘in reality’ anamorphoses. My interpretation in Vermeer’s Camerawas that Vermeer traced the images of the virginals twice with his camera obscura, but did not copy the real decoration of the lids - which might not even have been pictorial - finding them disturbingly foreshortened and distorted. He was left with two empty quadrilaterals, which he filled with views that are comprehensible and ‘natural’ seen at these angles - although he has still compressed the Groenewegen somewhat in width.

Notice how Vermeer has given a black border to the Groenewegen. As we see the lid in the ‘Woman Standing’, this border is of equal width at the top and the side. This would mean that, on the instrument itself, the border at the side would have had to be much wider than the border at the top. (Of course, no person ever actually saw these fictive decorations from the front.)

John Sharp would have insisted on the proper mathematical description. The transformations are true perspectivities, relative to the theoretical viewpoints of Vermeer’s paintings. Vermeer fixed these viewpoints and painted frontal views. I projected the views back on to the notional oblique planes of the virginals, to generate the anamorphic versions.

- See for example Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2001 pp.402-406

- Gregor J M Weber, ‘Vermeer’s Use of the Picture-within-a-Picture: A New Approach’, in Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker eds, Vermeer Studies, Studies in the History of Art No.55, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, pp.295-307: see p.297

- Philip Steadman, Vermeer’s Camera, Oxford University Press 2001: see pp.115-117