Architects in fiction, Part 1

Women’s magazines of the post-World War II years published romantic short stories in which the heroine’s dream was to marry an architect: a man with an artistic side who nevertheless could bring in a regular salary. The Goodreads website listed 59 ‘romance fiction’ novels in print in 2019 with architects as leading characters. The profession has not been treated so kindly in the literary novel.

Pecksniff

Mr Pecksniff in Dickens’s *Martin Chuzzlewit *is a hypocrite who lectures others on morals but fails to follow his own advice. “Some people likened him to a direction-post, which is always telling the way to a place and never goes there.” Despite advertising himself on his brass plate as PECKSNIFF, ARCHITECT AND LAND SURVEYOR, he has never in fact built anything. His income is derived wholly from taking in paying pupils.

“His genius lay in ensnaring parents and guardians, and pocketing premiums. A young gentleman’s premium being paid, and the young gentleman come to Mr Pecksniff’s house, Mr Pecksniff borrowed his case of mathematical instruments (if silver-mounted or otherwise valuable); entreated him, from that moment, to consider himself one of the family; complimented him highly on his parents or guardians, as the case might be; and turned him loose in a spacious room on the two-pair front; where, in the company of certain drawing-boards, parallel rulers, very stiff-legged compasses, and two, or perhaps three, other young gentlemen, he improved himself, for three or five years, according to his articles, in making elevations of Salisbury Cathedral from every possible point of sight; and in constructing in the air a vast quantity of Castles, Houses of Parliament, and other Public Buildings.”

Otto Friedrich Silenus

In Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, Mrs Best-Chetwynde commissions a house from a struggling young German architect, Otto Friedrich Silenus. Aged just 25, the self-styled ‘Professor’ Silenus has worked in Moscow and at the Bauhaus in Dessau, although at present he is ‘starving resignedly’ in a bed-sit in Bloomsbury. Mrs Best-Chetwynde found him through reading about his “rejected design for a chewing-gum factory which had been reproduced in a progressive Hungarian quarterly.” She tells him that she wants something ‘clean and square’ for her house, and then goes away on a long trip.

When a journalist comes to see the ‘surprising creation of ferro-concrete and aluminium’ under construction, Silenus tells him “The problem of architecture as I see it is the problem of all art—the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form. The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men. I do not think it is possible for domestic architecture to be beautiful, but I am doing my best. All ill comes from man: please tell your readers that. Man is never beautiful; he is never happy except when he becomes the channel for the distribution of mechanical forces.”

Watching the journalist disappear down the drive, Silenus munches a biscuit gloomily and muses to himself: “I suppose there ought to be a staircase. Why can’t the creatures stay in one place? Up and down, in and out, round and round! Why can’t they sit still and work? Do dynamos require staircases? Do monkeys require houses? What an immature, self-destructive, antiquated mischief is man!”

Later Mrs Best-Chetwynde’s guests discuss Silenus. His house is ‘extraordinarily interesting.’ “He’s got right away from Corbusier, anyway.” “If people only realized, Corbusier is a pure nineteenth-century, Manchester school utilitarian, and that’s why they like him.”

Howard Roark and Peter Keating

The plot of Ayn Rand’s 700-page epic *The Fountainhead *is centred on architecture, and the cast of characters features many members of the profession. The book is set in New York in the 1920s and 30s, against the background of the stylistic battle between European modernism and American Beaux Arts classicism. The two main protagonists Howard Roark and Peter Keating study architecture together at the Stanton Institute of Technology. Peter Keating graduates with the highest honours, a gold medal from the Architects’ Guild of America, and a scholarship to study in Paris. Howard Roark is expelled.

Roark, the modernist, has complete belief in himself, his abilities and his art. He is not personally arrogant, but is utterly unable to make compromises in design, and works on projects with relentless focus. A colleague says to him: “It’s uncomfortable to be in the same room with you. Tension is contagious, you know.”

“What tension? I feel completely natural only when I’m working.”

“That’s it. You’re completely natural only when you’re one inch from bursting into pieces. What in hell are you really made of, Howard? After all, it’s only a building. It’s not the combination of holy sacrament, Indian torture and sexual ecstasy that you seem to make of it.”

“Isn’t it?”

Roark’s unwillingness to cultivate clients or give them what they want means that he is frequently sitting in an empty office while his debts mount. Sometimes he takes on work as a building labourer. He gets a commission from an eccentric philanthropist Hopton Stoddard to build the Stoddard Temple of the Human Spirit, and is given a free hand. He designs a small grey limestone building. Stoddard returns from a trip and is appalled by the building’s blasphemies. Four other architects are hired to convert the Temple into the Hopton Stoddart Home for Subnormal Children, by the addition of Venetian balconies, ‘cubistic ornament’ and a ‘semi-Gothic’ spire. Peter Keating is responsible for the white marble ‘semi-Doric portico’.

Keating meanwhile has been climbing the ladder of commercial success. He moves in New York’s fashionable society, flatters his clients, and is happy to comply with their wishes for Greek temple fronts. In the end he becomes disgusted with himself and loses all relish for the position he has reached at the head of his profession.

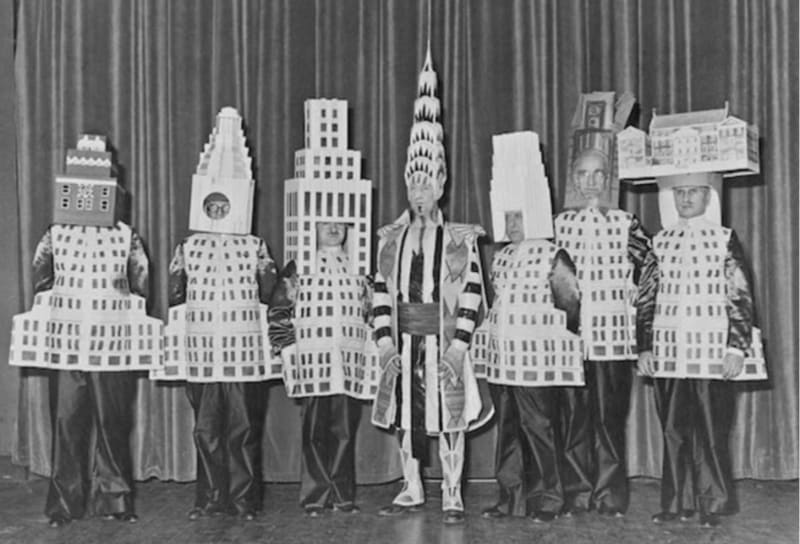

Along the way Rand recreates some real events, lightly disguised, as for example the famous Beaux Arts Ball of 1931 when skyscraper designers came dressed as their own buildings. In Rand’s version Peter Keating “looked wonderful as the Cosmo-Slotnick Building. An exact papier-mêché replica of his famous structure covered him from head to knees; one could not see his face, but his bright eyes peered from behind the windows of the top floor, and the crowning pyramid of the roof rose over his head.”

Various speakers lecture from time to time on architecture, although one is never quite sure whether Rand’s intentions are serious or satirical. Gordon L Prescott says that “The correlation of the transcendental to the purely spatial in the building under discussion [the Stoddart Temple] is entirely screwy. If we take the horizontal as the one-dimensional, the vertical as the two-dimensional, the diagonal as the three-dimensional, and the interpenetration of spaces as the fourth-dimensional… we can see quite simply that this building is homaloidal, or—in the language of the layman—flat. The flowing life which comes from the sense of order in chaos, or, if you prefer, from unity in diversity, as well as vice versa, which is the realization of the contradiction inherent in architecture, is here absolutely absent.”

Many episodes in the book are threaded together by the person of Dominique Francon, an icy affectless beauty who works as an architectural journalist on The Banner, a populist muckraking newspaper. (Is she Rand’s alter ego?) In sequence: Dominique lusts after Roark when she sees him drilling granite in a quarry, and he effectively rapes her; she poses for a nude statue to be installed in the Stoddart Temple; she marries and divorces Keating; she marries Gail Wynand the editor of The Banner; she commits adultery with Roark and alerts the press, in order to engineer another divorce; and ends up marrying Roark, who she has always really loved.

With the threat of a deadline, Rand apparently completed the final chapters of *The Fountainhead *at great speed under the influence of Benzedrine, and it shows. The plot becomes ever more incredible. Keating is commissioned to build a large public housing project, Cortlandt Homes, and is unable to rouse himself to the task. He persuades Roark to make the design for him anonymously and in secret. Roark’s condition, as always, is that he has complete control and the scheme is built exactly to his plans. Inevitably this does not happen. Other hands are brought in, despite Keating’s efforts. In the end Roark decides to dynamite the unfinished development, and allows himself to be caught in the act by the police. At the trial, he makes a long speech about his philosophical and artistic principles. He has blown up Cortlandt because it has been ‘mutilated by second-handers’. The jury declare him not guilty.

Gail Wynand hires Roark to construct the Wynand Building, the tallest skyscraper in New York. In the book’s final scene, Dominique is being carried upwards on the outside hoist of the building’s rising frame, to meet Roark at the very summit.

As a footnote: Rand based Howard Roark on Frank Lloyd Wright and sent the first two chapters to Wright for his reactions. He failed to read them, so when she finished the manuscript, Rand sent him the whole book. She said “I have taken the trouble to write this, and you are the model for the main character, so the least you can do is to read it.” Wright read it and thought it was ‘damn good’. When plans were in train to turn the book into a movie, the producers offered Wright $180,000 to design the sets. In true Roark style, he said he would do it only if could direct the film. They turned him down. Bruce Goff, who tells this story, said “It is too bad they didn’t take him up on it because that would have been a curious affair, no doubt.”

Charles Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit was published in book form by Chapman and Hall in 1844; Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall was also published by Chapman and Hall in 1928; Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead was published by Bobbs Merrill in 1943