Boy (and girl) architects and their toy buildings, Part 2

Wooden or stone toy building blocks are piled up under gravity, each block resting on those below – like the pyramids. The precariousness of towers, bridges and overhangs is all part of the fun. The Lilienthals argued that their stones gave greater structural stability than wooden blocks, because of their greater weight and rougher surfaces. Even so, the Art Department of the Anker company resorted to using glue in the construction of their largest and most complex display models.

Anker also sold special sets of scaled-down replicas of real bricks and half-bricks for training apprentice bricklayers. Presumably these were laid with actual mortar. The English toy Brickplayer had stone blocks like Anker, but these were stuck together with a ‘mortar’ made of flour and powdered chalk, a mixture that is soluble in water, so that the models could be soaked and taken to pieces again. Children apparently found this too fiddly and time-consuming to be enjoyable. But Brickplayer was at least a faithful imitation of traditional masonry construction.

Brenda and Robert Vale are known for their pioneering work on ‘autonomous’ houses that rely on local renewable energy sources, and are independent of networked power and water supplies. The Vales are also lifetime collectors of construction toys, and have written a book on the subject, Architecture on the Carpet. The book concentrates largely on 20th century British and American examples. (Fröbel appears only fleetingly.) The Vales’ main theme is how different toys have been designed to recreate different architectural styles, either contemporary or harking back to vanished pasts. The book however raises, less explicitly, another question: the relationship between the methods used to connect the components in toys, and equivalent or contrasting techniques used in real buildings.

Lincoln Logs, still on sale today, were designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s second son John around 1916. The redwood pieces are in the shape of untrimmed tree trunks, notched so that they can be stacked to form walls and roofs. The reference obviously is to the log cabins of the American West, built by a similar process. With enough pieces, whole miniature frontier towns can be put together. ‘Lincoln’ is probably an allusion to President Abraham, famously raised in a log cabin.

Here then is another case where the toy’s method of assembly follows reasonably closely the real technique. (Although there were also wooden wheels supplied with the Logs with which one could build carts, stagecoaches and - according to one set of instructions - a very improbable Greyhound Bus, which looks like something on which the Flintstones might have gone touring.) John Wright worked for his father on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, whose foundations helped the building to survive the earthquake of 1923 relatively undamaged. It has been suggested that Lincoln Logs were inspired by the wooden interlocking members of those foundations.

Another toy of the period, Bilt-E-Z (the letters to be given an American pronunciation) is a different matter. This was a kit for building skyscrapers. The pieces are squares of tinplate, the edges folded in such a way that the plates can be joined edgewise. The wall pieces contain doors and windows, and there are other squares for flat roofs. Although Bilt-E-Z was manufactured in Chicago, where the skyscrapers of the period are all cut off flat at the top, it could also be used to make stepped pyramidal buildings in the New York ‘setback style’ effectively mandated by the city’s Ordinance of 1916. In reality, all the skyscrapers in both cities depended structurally on their metal frames, filled in with brickwork or other materials whose function was to close the envelope, and which had no structural role.

In Bilt-E-Z by contrast the panels *are *the structure. From a strictly engineering point of view, there are closer affinities between Bilt-E-Z and the types of prefabricated concrete system introduced after World War II, whose wall panels were indeed structural, and there was no separate frame. In Britain the reputation of such methods was greatly harmed when there was a gas explosion in a high-rise block of flats called Ronan Point in 1968. Some panels were blown out, others above fell, and the building partly collapsed.

Bilt-E-Z was advertised with the slogan ‘As the boy builds the toy, the toy builds the boy’. The Vales point out that on the boxes of many old construction toys, and in the instruction books, there are pictures of boys (and their fathers) working away, while girls (and their mothers) look on admiringly, or are painting the finished models. Designs for train stations are suggested for the boys, and dolls’ houses for the girls. On the Bilt-E-Z boxes however a girl and a boy seem to be taking equal credit for the skyscraper skyline.

Models of buildings with true supporting frames can be made with the American Tinkertoy and the British Meccano, although both toys are intended first of all for constructing machines and vehicles. Tinkertoy structures are made from rods fitted into holes in spools that serve as junction pieces – like the rods and dried peas of the Fröbel gift. The long flat girders of Meccano with their punched holes can be bolted together into frameworks for buildings or bridges. The English ‘High Tech’ architects Richard Rodgers and Norman Foster both played with Meccano as boys, and one can certainly detect a Meccano-like aesthetic in Foster’s Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, Rogers’s Lloyds Building in London, and above all in Rogers’s Pompidou Gallery in Paris, designed with Renzo Piano, its structure and services all exposed on the exterior.

Indeed the Pompidou was described explicitly by the architects as ‘a giant Meccano set’, whose components could, they claimed, be rearranged to offer flexibility in use. In fact, as the Vales point out, the Pompidou is quite unlike Meccano in that the structural elements were not standardised but were manufactured as one-offs, and the building has never been greatly altered. Arguably a building with closer affinities to Meccano is the Crystal Palace, which was dismantled when the Great Exhibition ended, and the standard pieces re-erected in South London to make a quite different shape of building.

Castos was an English toy of the 1940s that imitated precast concrete construction. The kit contained wooden pieces for assembling moulds, and the ‘concrete’ was plaster of Paris. One might have expected the blueprints to be for modernist flat-roofed houses or aircraft hangars. But at least some of the designs were for recreating medieval stone buildings: a 7th century church in Sunderland, a 13th century bridge in Monmouthshire. Castos does not seem to have been a great success. Perhaps it was too messy, and the delays, waiting for the parts to set, too frustrating.

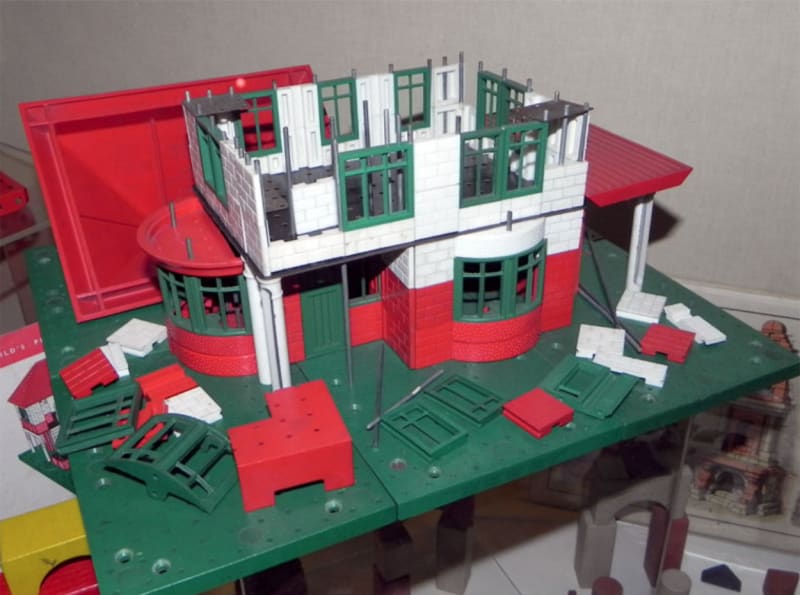

The most curious of all kits for making buildings, from a structural point of view, was Bayko. The pieces – white walls, green windows and red roofs – were all precisely adapted to constructing the kinds of detached and semi-detached houses that appeared in their hundreds of thousands in the suburbs of Britain between the two World Wars. The way the models were held together however was bizarre. One pushed thin vertical metal rods into a baseplate and carefully threaded the pieces, including perfect period bay windows, onto these rods. It was as though there were scaffolding poles inside the walls. The results resembled the real houses exactly. But no ‘Bypass Variegated’ houses, as the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster called them, were ever threaded on thin rods.

Brenda and Robert Vale, Architecture on the Carpet, Thames and Hudson 2013

All of the toys mentioned in both parts of this curiosity can be bought online, either new, or second hand for sale to collectors