Boy architects and their toy buildings, Part 1

Plato said that “if a boy is to be… a good builder, he should play at building toy houses… and be provided by his tutor with miniature tools modelled on real ones.” From the late 18th century we can follow this learning process in action. Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Maria Edgeworth in their book *Practical Education *of 1798 recommended that the nursery be equipped with “pieces of wood of various shapes and sizes, which [infants] may build up and pull down”, and that older children might make ‘models of architecture’ from cardboard and glue. In the 1830s the German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel developed these kinds of ideas into a complete teaching system for the ‘kindergarten’ (Fröbel’s term) in which educational toys known as ‘gifts’ played a central role.

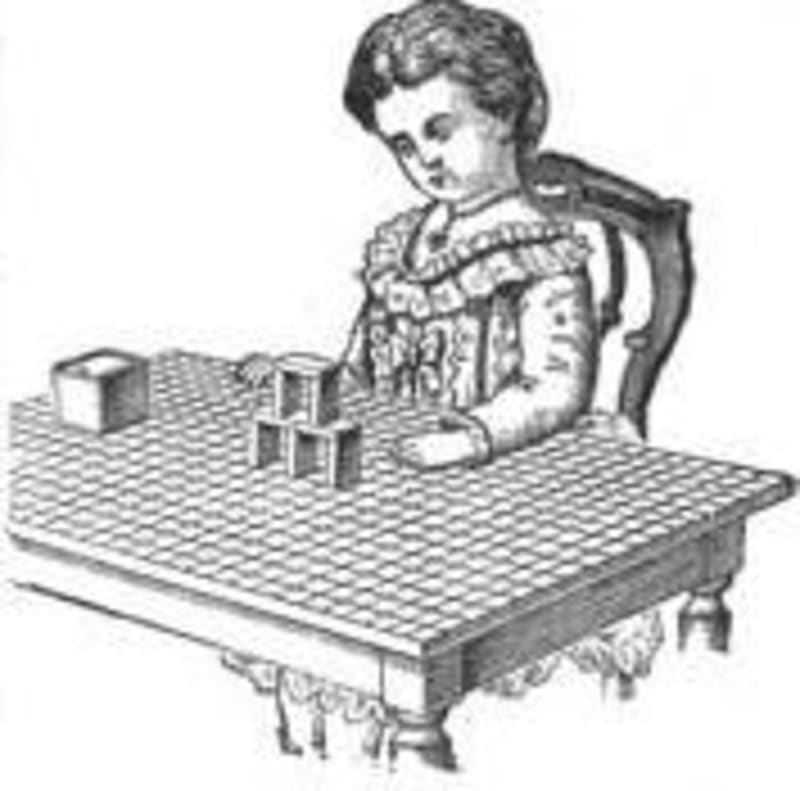

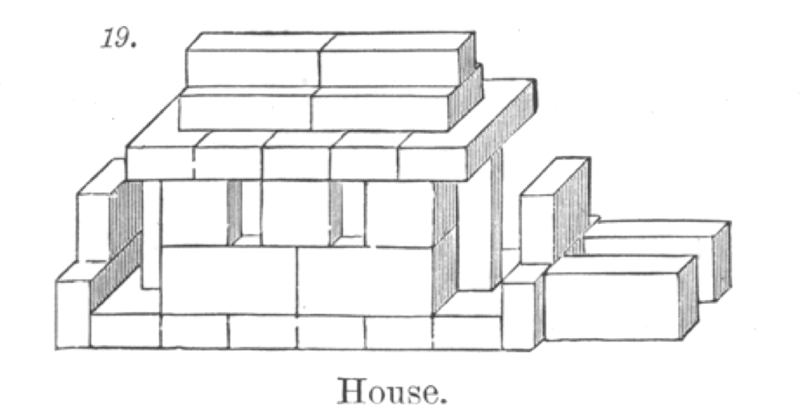

The gifts are numbered in order. Numbers 3 to 6 are sets of wooden blocks of increasing variety of form, from cubes only in Gift 3, to cubes, slabs and triangular prisms in Gift 6. Fröbel specified that when working/playing, the child should sit at a table with a gridded top on which to place the blocks. Fröbel had previously worked in Berlin with Christian Samuel Weiss, one of the pioneers of modern crystallography. The laws of symmetry and the spatial packing of elementary forms, which play a central part in that subject, find their clear expression in the patterns made with the kindergarten blocks. Other exercises involve weaving paper strips, arranging flat tiles, and making framework structures out of toothpicks with semi-dried peas for the joints.

In 1876 Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother Anna, herself a teacher, bought her nine-year-old son a set of Fröbel gifts at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Much has been written about young Frank’s fascination with these blocks and their influence on his later design work, not least by Wright himself. As he says in his Autobiography: “For several years I sat at the little kindergarten table-top ruled by lines about four inches apart each way making four-inch squares; and, among other things, played upon these ‘unit-lines’ with the square (cube), the circle (sphere) and the triangle (tetrahedron or tripod)—these were smooth maple-wood blocks. All are in my fingers to this day.”

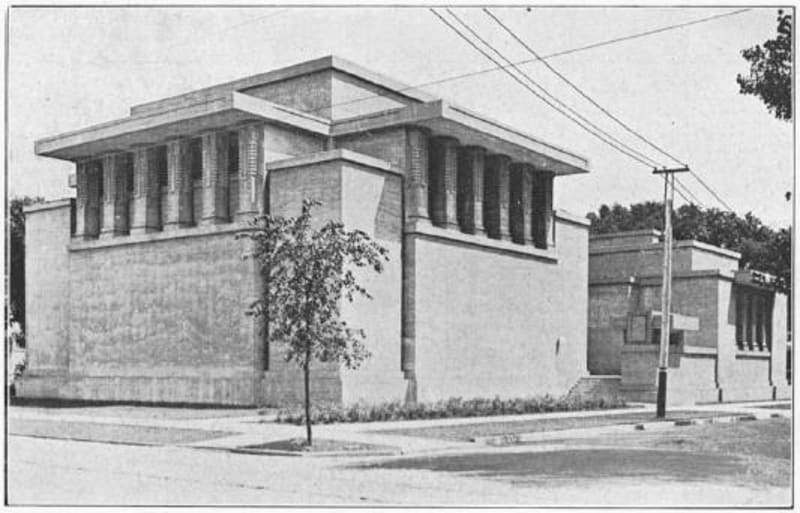

Wright writes about his mission to ‘destroy the box’ of traditional architecture, with its separate rooms packed inside the rectangular envelope of the external walls. Instead he conceives of buildings in terms of solid blocky elements – large chimney stacks, piers, parapets, oversailing flat roofs – and the spaces created between them. Rooms flow one into another, and the boundary between outside and inside is less sharply defined. We can see the sculptural affinities between a model house made with the sixth Fröbel gift and Wright’s Unity Temple in Chicago of 1908.

The plans of other Wright buildings have the symmetries, especially the cyclic or pinwheel symmetries, of patterns made with the various gifts. The British architect Richard MacCormac, whose own work owes something to Wright and who wrote about Wright and Fröbel, emphasises that the relationship is not just one of formal similarities. It depends as much on the ‘essentially abstract organisational discipline’ that Wright acquired in the kindergarten.

Wright is the architect in whose work this discipline is expressed most strongly. But Le Corbusier also had a Fröbel education, as did the visionary American engineer Buckminster Fuller, famous for his domes and ‘tensegrity structures’ built from jointed rods. Fuller says that these had their genesis in the Fröbel gift with sticks and dried peas.

Gustav Lilienthal was a German artist and architect who worked in the 1870s on the design of instructional wooden bricks for the educator Jan Georgens, a friend of Fröbel. Gustav and his brother Otto had the idea that the blocks might be better made of cast stone, and devised a recipe that combined sand, powdered chalk, and colouring, with linseed oil as the binder. (Otto is more famous as one of the pioneers of manned flight: the bat-like gliders in which he travelled hundreds of metres owed much to Leonardo da Vinci.)

The brothers had little commercial success with their invention and sold the rights to an industrialist Friedrich Adolph Richter, who marketed them under the name Anker [Anchor] blocks. They were sold internationally and are still manufactured today by the Goki company. They were the most successful construction toy ever produced, until Lego conquered the playroom after World War II. George F Hardy, historian of the Anker company, reckons that between 3 and 5 billion stones have been sold since the 1880s.

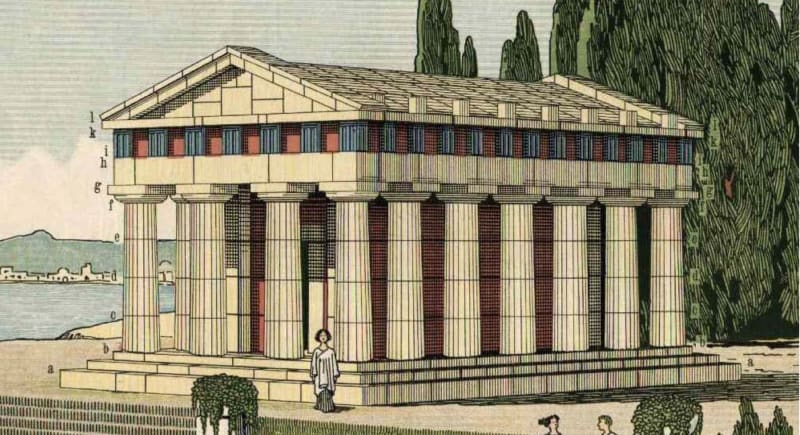

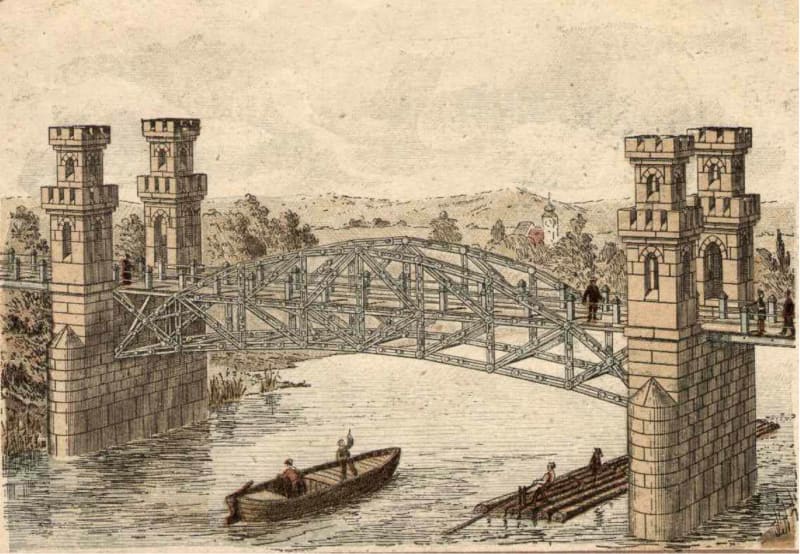

Richter sold boxed sets of blocks, the designs of which were simple at the outset but became much more complex. They were conceived less as instruments for kindergarten exercises, more for constructing ever more realistic models of historic German buildings. At first there were just three colours of block: brick red, slate blue and limestone white. Other colours were added later. Blueprints and illustrated instruction books were provided. Hundreds of different specially-shaped blocks were introduced, including for example parts with which to build an authentically detailed Doric temple. The Anker art department designed castles and cathedrals, requiring thousands of stones, that were exhibited at trade fairs. A series of bridge designs used the stone blocks for the supporting towers and piers, and a system of metal bars and plates – like the British toy Meccano – for the roadways.

Later in his career Gustav Lilienthal became involved in housing reform, and devised a system of prefabrication for low-cost houses. The system was called Terrast and used pre-cast concrete slabs that resembled much-enlarged Anker blocks. Indeed, one of the patents for Terrast cited an earlier patent for the Lilienthals’ original toy. Terrast was not a success. But in the 1920s Anker blocks were to provide the inspiration for another programme of experiment with prefabricated buildings at the Bauhaus in Dessau.

There was a shortage of housing in Germany after World War I, and the director of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, came to believe that this crisis could be solved through a combination of prefabrication and mass production. Gropius had played with Anker blocks as a child. He imagined “a house made up of variable set pieces, that are produced in stock and can be put together in a combinatorial way, say, in the manner of an Anker-Steinkasten [Anchor stone box], but on a larger scale.” The architectural historian Atli Magnus Seelow describes how Gropius saw in Anker blocks several of the characteristics required in (full-scale) systems of prefabrication: standardised components made in a factory, with modular dimensions, so that the parts fit together and are interchangeable.

Gropius and his partner Adolf Meyer exhibited two designs at the Bauhaus in 1923: the Honeycomb system, and the significantly named Big Construction Kit (Baukasten im Großen). The latter comprised six large modular components with which to build ‘house-machines’. Unfortunately, like Lilienthal’s Terrast, these projects also proved to be premature and failed to achieve the reductions in cost and time on site that they seemed to promise.

So the teachings of Fröbel rippled through the architecture of the first half of the 20th century. In 2008 the Lego company launched its ‘Landmark Architect’ series: specialised kits for building models of great monuments of the modern movement, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s house Fallingwater. The wheel comes full circle: full-size buildings with debts to Fröbel are translated back into toy blocks.

Richard MacCormac, ‘Froebel’s kindergarten gifts and the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright’, Environment and Planning B, Vol.1, 1974, pp.29-50

George F Hardy, Richter’s Anker (Anchor) Stone Building Sets, 2013, online at www.ankerstein.ch

Atli Magnus Seelow, ‘The construction kit and the assembly line – Walter Gropius’ concepts for rationalizing architecture’, Arts, Vol.7 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040095