Christopher Wren and friends watch the bees

Bee-keepers in England used to keep their bees in skeps: upturned straw or wicker baskets with small openings for the bees to come and go. There were no frames inside to which the bees could attach their honeycombs, and they fixed them directly to the baskets. There were several disadvantages for the apiarist. It was not possible to observe the bees, to check for diseases, or see when they were swarming. And when the time came to harvest the honey and wax, the skep was dismantled, and the bees were often deliberately killed.

In the 1650s a group of English gentleman gardeners and natural philosophers, several of them founder members of the Royal Society, became interested in bee-keeping and in new forms of hive, closer to modern designs. These consisted of separate wooden boxes that could be stacked up vertically and lifted off as necessary, with removable frames for the combs. They had glass windows through which the occupants could be watched. It seems that a Gloucestershire clergyman, William Mewe, was the original inventor of these ‘glass hives.’ Mewe wrote that it was his habit to look in on the bees after dinner, and to offer his friends a ‘diary of the bees’ negotiations’.

Mewe sent a model of his design to John Wilkins, Warden of Wadham College in Oxford and author of a wonderfully entertaining book on Mathematical Magick. Wilkins installed some glass hives in the Wadham gardens. His friend the diarist John Evelyn visited in 1654 and was very taken with their architecture, describing the hives as “built like Castles *and *Palaces” decorated with sundials, little statues and weathervanes. Evelyn made a drawing, and Wilkins gave Evelyn an empty hive for his gardens at his country house Sayes Court.

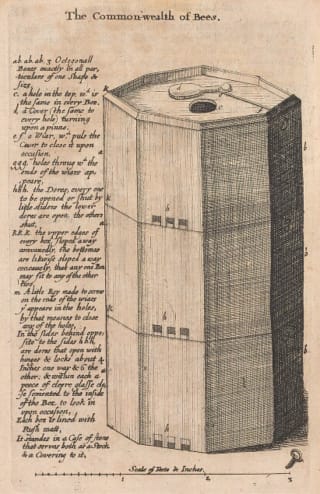

Evelyn included a copy of this drawing in his great encyclopaedia of gardening, the Elysium Britannicum, a work which occupied him for most of his life. In the book Evelyn writes that “…the Bee *is a rare *Architect, forming her hexangular [six-sided] cell for every foote or Angle…” Hives, he says, can be different shapes. “But the *Hexangular *seems to be the most agreeable because it resembles the forme of their cells.” In the key to his drawing however, in the original manuscript, Evelyn writes: “ABCD the Hive or Box an hexog… octoganal Forme.” (One can almost hear him cursing as he realises that the hive in the figure has eight sides, and crosses out ‘hexog…’.)

The small rectangles at the bottom of the classical arch are the doors for the bees. They can be closed with sliders. The glass windows are nowhere in evidence, either in the drawing or the key. But in the text, Evelyn writes: “Hives of this kind may have 2 or 3 windows to command a full view of their works, but two will be sufficient, because they [the bees] do not so much delight in the coldnesse of the glasse, & too great intromission of light distracts them.”

When Evelyn was in Oxford in 1654, Wilkins introduced him to a ‘much accomplished and very ingenious Gentleman, Fellow of All-Soules Colledge in Oxford, Mr Christopher Wren.’ Wren was then aged 22 and was to spend the next decade working on mathematics, astronomy and optics before turning to architecture. Wren did however play a minor role in the design of these beehives with windows.

Samuel Hartlib was a scientific friend of Evelyn and Wilkins who, amongst many other passions, was a devoted apiarist, and wrote a book on the subject, The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees, published in 1655. Evelyn went to see Hartlib’s hives. Perhaps it was Evelyn or Wilkins who introduced Hartlib to Wren. In any case, Hartlib’s description in his book of the ‘transparent hive’ designed by Mewe is illustrated with a figure by Wren, possibly the first architectural drawing that he ever made. It shows a structure built from three stacked *octagonal *boxes, again with small doors closed with sliders. The key mentions small sheets of glass serving as windows.

Wren did not just act as a draftsman. He tried out a hive of this design in practice. However, the bees did not quite follow the intended schedule. Wren wrote a letter to Hartlib describing how two swarms introduced to the hive had occupied the lower boxes but had not made use of the top storey. Wren had been hoping to remove this top box with its honey, leaving the two boxes below.

The hexagonal shapes of the cells of the honeycomb have the geometrical property of fitting closely together without gaps. The sizes of the cells are nicely adjusted to the bodies of the bees who work inside them. Architects – although not Wren himself – have sometimes designed buildings with hexagonal rooms. A single hexagon can make a good shape for a summerhouse or a gazebo. In buildings with many rooms whose shapes are simple hexagons, the geometrical discipline tends however to be a straitjacket - although one successful example is the Beehive Building for students in Saint John’s College Oxford. This was designed by Michael Powers of Architects’ Co-Partnership and completed in 1960. Every student has a ‘cell’.

Frank Lloyd Wright characteristically found a certain design freedom in a grid of small hexagons for several of his houses, including the Bazett House in northern California of 1940, and the Sundt House project of 1941. Here he was able to let his snaking walls follow the grid in three directions, to make many different sizes and shapes of room - triangles, parallelograms and hexagons.

John Evelyn, Elysium Britannicum or The Royal Gardens, ed John E Ingram, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 2001

Samuel Hartlib, The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees, Giles Calvert, London 1655

Christopher Wren [no relation] trogtrogbee, 22nd January 2017 ‘Sir Christopher Wren’s Beehive’, http://trogtrogbee.blogspot.com/2017/01/sir-christopher-wrens-beehive.html