Clonehenge

Of all the world’s great architectural monuments, which has most often been reproduced in three-dimensional facsimile? A fair guess is that it would be Stonehenge. Nancy Wisser’s wonderful *Clonehenge *blog gives photographs and descriptions (in 2020) of 97 permanent full-size replicas in many countries, of varying degrees of accuracy, plus a much larger number of temporary versions and scaled-down copies. More are being manufactured all the time.

English gentlemen were the first to erect copies in the gardens of their country houses. It seems that the very first was at Wilton House in Wiltshire, built in the 18th century, but nothing of this remains. (And it seems an unnecessary effort in any case, given that the real Stonehenge was just ten miles away.) There is a surviving Victorian copy at The Quinta in Shropshire, and another much freer version at Swinton Hall in Yorkshire, described by the archaeologist Christopher Chippindale as ‘a fantasy on the Stonehenge theme’. The real Stonehenge has at its centre a group of five *trilithons *in a horseshoe arrangement – a trilithon being a structure consisting of two vertical stones, with a third lintel stone laid across the top. At Alton Towers in Staffordshire, an amusement park since 1860, there is a very tall ‘Druid’s sideboard’ consisting of a trilithon standing on two trilithons. (Perhaps a ‘tri-trilithon’.)

Human effort on a prodigious scale was needed in the late Neolithic period to transport the stones great distances to Stonehenge and to trim and erect them. It has been suggested that the lintels might have been raised up by a process of rocking the stones back and forth and inserting wooden shims underneath. But in the 20th century, either heavy lifting machinery has been used to do the same job, or lightweight materials have been substituted for the sandstone and bluestone of the original.

The motivations of the re-builders have varied from sober through scientific to facetious. Colonel Samuel Hill directed the construction of a full-size concrete version by the Columbia River in Maryland, Washington State, in 1918-29. This has an austere dignity, fitting its role as monument to the dead of the Great War. Others have made replicas to test theories about how the original stones were put into position, or the supposed role of Stonehenge as some kind of astronomical observatory or celestial computer. In 2005 the British Channel 5 created a full-size reconstruction, in its complete unruined state, for a television programme, to test a theory about the orientation of Stonehenge to sunrise at midsummer and sunset at midwinter. This was made from styrofoam reinforced with cardboard tubes. (There is another Foamhenge, originally at Natural Bridge Virginia in the USA, which is now in Centreville VA. Being very light it is easily moved.)

The Clonehenge blog has a series of ‘henginess’ criteria for judging what qualifies as a clone. It must either look like Stonehenge; or be intended as a replica; or be called a replica by the public and the media; or have been built to test theories about the construction of the original; or work as a solar calendar; or be a structure surrounded by a ditch and a bank. On this basis, and some arbitrary prejudices, each replica is rated on a scale of 1 to 10 ‘druids’, where 10 is high. The Channel 5 Foamhenge scores 9 or maybe 9.5 druids.

Artists have been inspired to create their own idiosyncratic versions. There are many Stonehenge-like sculptures and fountains around the world. In Britain the elusive graffiti artist Banksy built a version out of portable toilet cubicles (‘Privyhenge’) for the Glastonbury music festival in 2007. For the year of the Olympic Games in 2012 the artist Jeremy Deller designed a pneumatic Stonehenge (‘Sacrilege’) that was transported around Britain. When inflated the stones erected themselves gradually like waking elephants, and visitors could bounce with abandon on the green ‘turf’.

Clonehenges can be, and have been, made out of almost any kind of elongated, roughly rectangular slab. Besides plastic foam, materials have included iron, wood, painted concrete, plaster on steel mesh, and straw bales. Fridgehenge in New Mexico was built by ‘slaves’ in loincloths as a protest against consumer culture and the planned obsolescence of white goods. Icehenge in Fairbanks, Alaska (9 druids) was built by delegates to the 41st Annual Surveying and Mapping Conference in 2007. It has since melted. Phonehenge, made from old red British telephone kiosks, is to be found at the Myrtle Beach amusement park in South Carolina. There have been at least three clonehenges built from automobiles, of which Carhenge in Alliance Nebraska has become an attraction with 35,000 visitors a year. The structure was put up over a weekend in 1987 by Tim Reinders and family as a monument to Tim’s father. Beyond this there have been endless edible miniature Stonehenges made from cake, jelly, gingerbread, cheese, bananas, biscuits, dog biscuits…

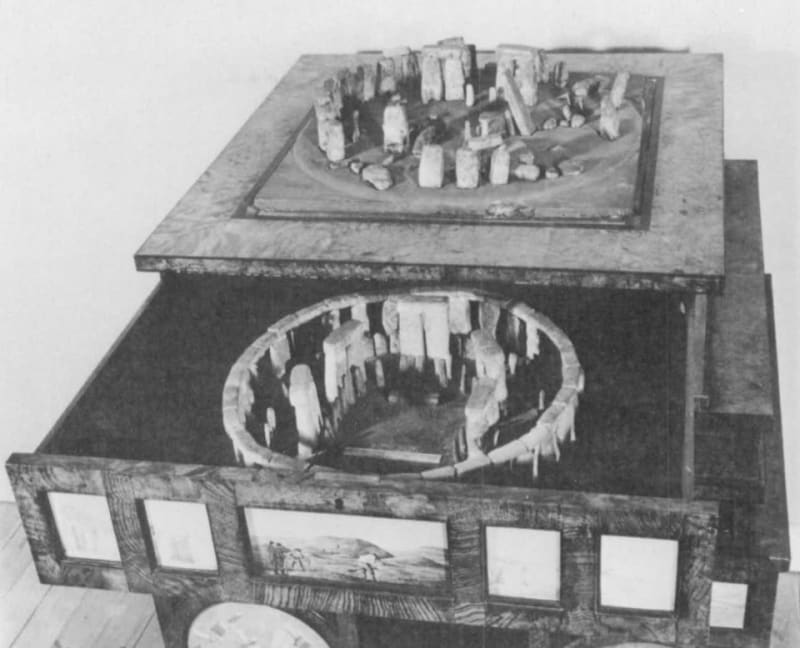

The first person to build scale models of Stonehenge seems to have been Henry Browne, the custodian of the monument at the start of the 19th century, who gave peculiar lectures on Ancient and Modern History. Browne produced two models, made of cork, in multiple copies. One showed Stonehenge ‘As it is’, the other ‘As it was’. They cost 7 guineas the pair. The photograph shows both models displayed in a cabinet of curiosities that once belonged to John Britton and is now in the Devizes Museum, together with a third model of the stone circle at Avebury. So here, in this digital cabinet of curiosities, is a real physical cabinet with the same subject of curiosity inside.

Many thanks to Nancy Wisser at Clonehenge: https://clonehenge.com ‘A blog about Stonehenge Replicas. We kid you not.’

Christopher Chippindale, Stonehenge Complete, Thames and Hudson, London and New York 1983, revised 1994

Christopher Chippindale, ‘John Britton’s ‘Celtic Cabinet’ in Devizes Museum and its Context’, The Antiquaries Journal, Vol.65, 1985 pp.121-138