Foreshortening in the forest

It is possible to create a picture in perspective which gives a powerful sense of space and depth without any straight lines that recede to vanishing points - indeed without any straight lines at all.

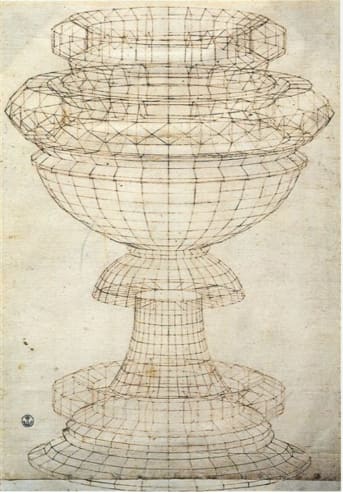

Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was an inventive pioneer of perspective in the period of intense activity that followed Brunelleschi’s rediscovery of the basic principles in the 1420s. Uccello painted battle scenes in which the broken lances of the combatants fall neatly in the direction of a central vanishing point. He made an extraordinary measured perspective drawing of a vase in which the surfaces are approximated by rectangular facets - exactly as curved surfaces were represented in ‘wire frame’ models in the early years of computer graphics.

Giorgio Vasari in his biography of Uccello tells a much-repeated story about the painter’s obsession with the subject. His wife “…was wont to say that Paolo would stay in his study all night, seeking to solve the problems of perspective, and that when she called him to come to bed, he would say: “Oh, what a sweet thing is this perspective!”[1]

Uccello’s last known painting made around 1470 is a panoramic scene of a hunt in a forest at night. The picture is now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The foliage of the trees is flecked with gold, which would have sparkled when the painting was seen by lamp or candle light. Here there are no perspective lines receding to vanishing points - with the possible exception of the bright streak at the right, which is perhaps a river or stream. The trees are scattered at random, not set out in lines. The effects of depth are achieved by foreshortening: the reduction in size with distance of the trees, horses, hunters, and dogs. Vasari writes that Uccello “introduced a way, method, and rule of placing figures firmly on the planes whereon their feet are planted, and foreshortening them bit by bit, and making them recede by a proportionate diminution; which hitherto had always been done by chance.”[2] Even the flowers among the grass on the forest floor are made smaller, the further away they are.

I asked Martynas Kasiulevicius to build a 3D computer model, not to reproduce the Uccello, but to illustrate these effects. This is constructed from three standard models of a tree, a horse, and a dog, repeated and set at different distances in the virtual space. The resulting image is a view in which foreshortening creates the entire illusion of depth.[3]

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans. Gaston Du C. de Vere, 10 vols, Philip Lee Warner, London, 1912-14: biography of Uccello in vol.2 p.140

- ibid p.132

- There is some additional effect of occlusion: the fact that objects nearer the view hide parts of objects further away.