Noon on the church floor

The camera obscura in its simplest and oldest form consists of a darkened room with a small hole made in a door or window shutter. An image of the sunlit scene outside is projected through the hole onto the opposite wall of the chamber. If there is no lens in the hole, the picture is generally faint, but one object – the sun – gives a sharp bright image. In the 16th and 17th centuries, churches and cathedrals were turned into giant camera obscuras. Holes were made in their roofs, and images of the sun’s disc were projected onto the floor. Long straight lines or *meridians *running north-south were marked with metal strips, carefully positioned and aligned such that the centre of the sun always fell exactly on the line at noon. As the days passed the position of the disc at mid-day advanced slowly along the line. The great size of the buildings meant the observations could be highly accurate.

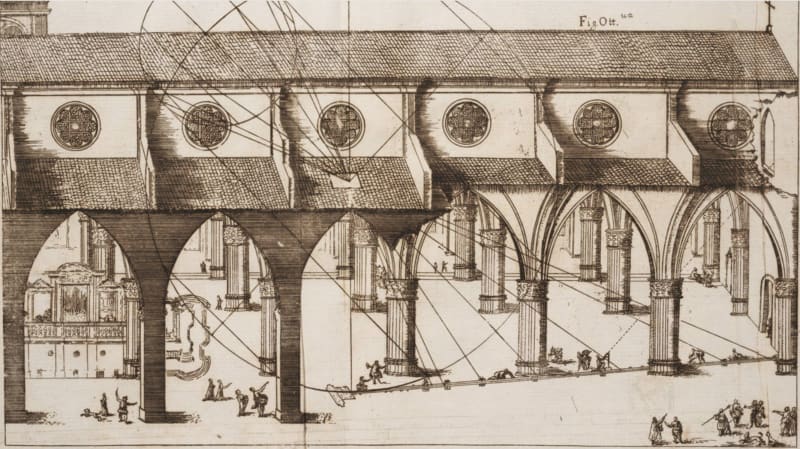

The historian of science John Heilbron has written a book about these instruments called The Sun in the Church. Several meridians are still in place, the most important and most accurate of which is at San Petronio in Bologna. The drawing shows the geometrical construction lines used in the design, the plate in the roof with the small hole, and the meridian on the floor, just managing to avoid the feet of the columns. The hole was decorated on the underside of the vault with a golden image of the sun’s rays. The photo below shows a detail of the inset metal strip itself. The stone panel straddling the line depicts a crab, the Zodiac sign of Cancer. Charles Dickens visited the church and thought it the only interesting sight in Bologna: “where the sun beams mark the time among the kneeling people.” There are seven more instruments of this type in Italian churches including the cathedrals of Florence, Milan and Palermo; one in Saint-Sulpice in France; and the remains of a meridian in the cloisters of Durham Cathedral in England. Yet another is housed in the Torre dei Venti (Tower of the Winds) in the Vatican, not open to the public.

Despite what Dickens assumed, the primary function of the meridian was not for telling the time of day (other than at noon). It had a much larger ecclesiastical purpose, which was to determine the date of Easter. The Catholic Church is conventionally thought of as the enemy of astronomy, on the strength of its prosecution and punishment of Galileo for his heretical belief in the Copernican model of the universe, centred on the sun. In fact, as Heilbron emphasises, the Church has consistently supported astronomical research since the Middle Ages, and many leading astronomers have been members of the Jesuit Order.

The date of Easter was problematic, since it was not and is not fixed to a specific day of a specific month, like Christmas Day. Instead the date was determined by the Council of Nicaea in 325AD according to a rule: it should fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. There are two equinoxes in the year, in spring and autumn: these are the days when there are exactly 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. So at any location the clergy could in principle get the day right by following the rule (assuming the full moon was visible.) But there were difficulties. The Council of Nicaea’s formula meant that Easter might fall on different days in different parts of the world, which for the Catholic Church and its universal ambitions was liturgically unacceptable. As Heilbron says, if people worshipped on the wrong day, “souls were at risk”. The Church wanted to work out a standard date for Easter each year and inform congregations everywhere, well in advance.

During the course of a year, the sun’s image at noon moves along the whole length of the meridian, and back again. The ends mark the summer and winter solstices. Between these is a point that marks the position of the spring and autumn equinoxes – not half way along the line by distance, but half way in terms of the angle made by the sun. The meridian was thus a precision instrument for measuring the exact number of days between successive equinoxes, that is to say, the length of the solar year. This was the key to predicting the date of Easter.

The first of these instruments was begun for Cosimo de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany in the 1570s. Cosimo commissioned a Dominican friar Egnazio Danti, a mathematician and astronomer, to turn the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence into a camera obscura with a meridian. However, Cosimo died before the work was finished. Danti lost his job and moved to Bologna, where he built a smaller version, and then a larger one in San Petronio, which however turned to be misaligned. Danti also designed the meridian in the Vatican, where he had the walls of the Tower painted with allegorical figures of the Winds, tossing St Peter’s boat in a storm. In 1655 the Bologna instrument was redesigned and rebuilt by the astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, celebrated for his observations of the rings of Saturn. The drawing at the head of this article is by Cassini.

By Cassini’s time however, the function of the meridians was already being made redundant by measurements using telescopes. They remained useful nevertheless for checking the accuracy of clocks at noon. They also turned out to have another application in the upkeep of the churches themselves. Over time the parts of a large building move: roofs sag and floors deform. At the Cathedral in Florence the meridian has been used to monitor these movements, by measuring how far the sun’s image has diverged from its original position when the instrument was first installed.

J L Heilbron, The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass, 1999