Operation Teapot

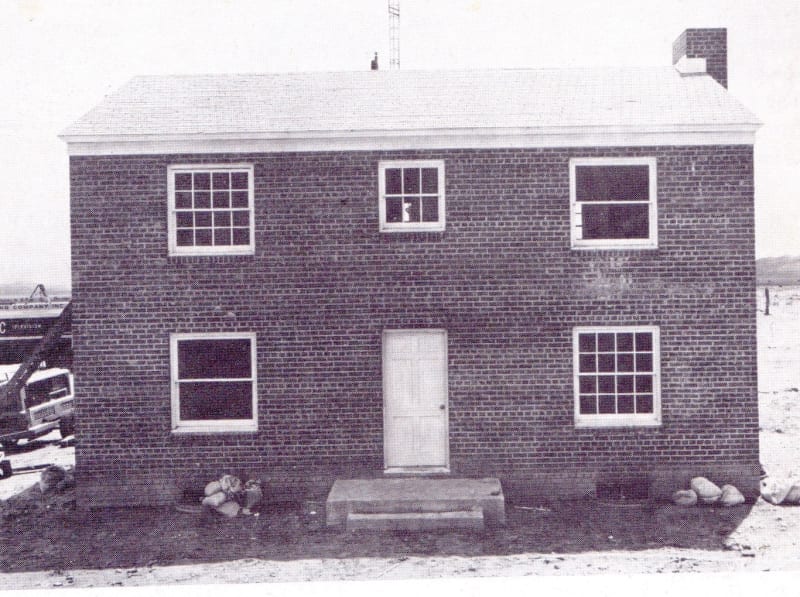

In 1955 the US Department of Defense erected a number of buildings in the Nevada desert and exposed them to a nuclear explosion. The interiors were fully furnished, and populated with tailors’ dummies. The photos show a brick house before and after the blast. The impact was also filmed. The project was known as Operation Teapot. The purpose was of course to gather data for making predictions of the effects of weapons dropped on cities in some future nuclear war. Other information had been collected from surveys of the ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Such experiments were made impossible a few years later by the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963, which put a stop to further testing of nuclear weapons other than under the ground. Instead data were fed into computer models. It is right to be sceptical about theoretical computer predictions of complex phenomena in many applications. But on this particular subject, as the futurologist Herman Kahn wrote, “It will do no good to inveigh against theorists. In this field everybody is a theorist.” Kahn was the author of On Thermonuclear War, a book whose title does not lead one to expect its many jokes and jibes against bureaucrats. (Kahn was one of several models for *Doctor Strangelove *in Stanley Kubrick’s film.)

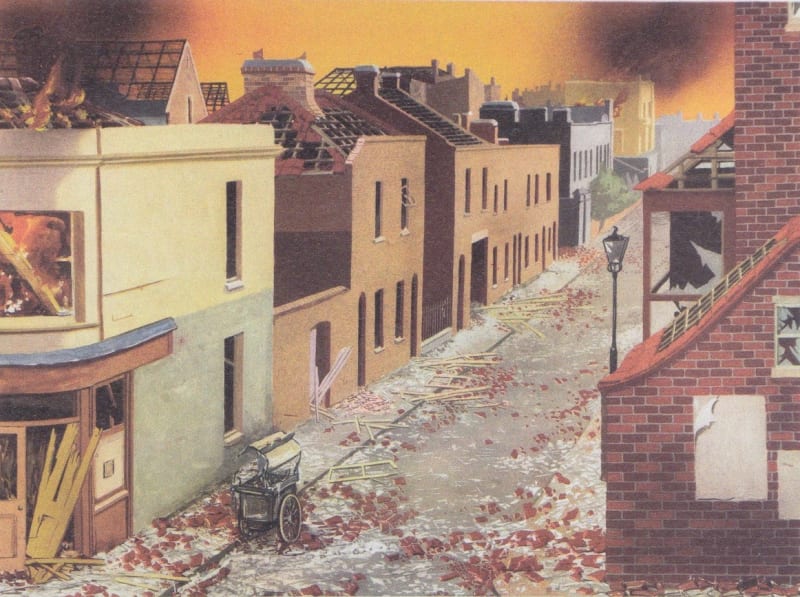

In the 1980s the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Britain was re-energised in opposition to proposals to install medium-range ground-based nuclear missiles in Europe. The British Home Office was making plans for the defence of the civilian population in the event of war, including the printing of its notorious leaflet, Protect and Survive, to be distributed to all households, advising the occupants to prepare sandbagged ‘refuge rooms’ under the stairs. Those caught outdoors should lie in ditches. “On hearing the all-clear… you may resume normal activities.” The figures below reproduce posters produced by the Home Office in 1958 for training civil defence workers, again showing ‘before’ and ‘after’ an attack, but imagined in a pair of paintings. Nuclear weapons have been dropped on a Victorian city. (Notice the unscathed milk cart and gas lamp.)

The Home Office Scientific Research and Development Branch built a computer model with which to explore different scenarios for attack on the country. The work was not made public; but in 1982 Stan Openshaw, a geographer from Newcastle University got hold, by devious means, of a Home Office technical report describing their methods. This allowed Openshaw and colleagues in the campaigning group Scientists Against Nuclear Arms to reconstruct the Home Office model, and compare it with a model built using the methods of calculation published in the open literature by the US Department of Defense. They found very large differences. Overall, American models were predicting roughly twice the numbers of deaths and injuries as the Home Office, for identical patterns of attack.

There were several causes: but one reason in particular had to do with the effects of nuclear blast forces on buildings. These forces are measured in pounds per square inch as *overpressures *– pressures in excess of normal atmospheric pressure. The house in Operation Teapot was subjected to a maximum overpressure of five pounds per square inch. This force would be produced, for example, by a 1-megaton weapon, burst at ground level, at a distance of five kilometres (three miles). (The US Department of Defense measures these distances in ‘kilofeet’.)

The Home Office and the Americans did not disagree in their figures for these maximum pressures, at different distances from bombs of varying sizes. But they differed radically in their assumptions about the numbers of casualties that would result. Eventually the explanation emerged. The British were still using statistics, forty years on, from the Blitz on London in the Second World War. Chemical high explosives – allowing for the huge differences in power – do not however cause similar damage at the same levels of overpressure as nuclear weapons. This is because, in a nuclear explosion, the blast wave lasts much longer.

During the Blitz there was one death for every one ton of German bombs. At Hiroshima and Nagasaki there were six deaths for every ton, measured in equivalents of high explosive. Casualties in Japan had other causes than blast: but the Home Office was also underestimating those. They were making questionable assumptions about the medical effects of exposure to radiation from fallout; and they were completely excluding any burn injuries and fires from the intense bursts of heat given off by nuclear explosions.

The purpose of erring so far in this direction was clearly to underplay the dangers and damp down any public concern. As the Home Office Minister Patrick Mayhew said in a radio interview in 1982, more realistic calculations if made public could be used to support an argument to “go neutral, non-nuclear and pull out of NATO.” In the same interview Mr Mayhew said however that he did not take issue with American methods of prediction, effectively renouncing his own Department’s work

Philip A Randall, Damage to Conventional and Special Types of Residences Exposed to Nuclear Effects,Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, Washington DC, March 1961

P R Bentley, Blast Overpressure and Fallout Radiation Models for Casualty Assessment and Other Purposes, Home Office Scientific Research and Development Branch, London, December 1981

Stan Openshaw, Philip Steadman, Owen Greene, Doomsday: Britain After Nuclear Attack, Blackwell, Oxford 1983 Chapter 9

Taras Young, Nuclear War in the UK, Four Corners Books 2020