Ornament and criminology

In 1910 Adolf Loos gave a lecture in Vienna that was prophetic for modern architecture in Europe. The title was ‘Ornament and crime’. Loos announced a great discovery that he was passing on to the world: “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.”

The houses that Loos designed for his rich Austrian clients are stark white boxes with flat roofs, completely free of any mouldings or articulation, the doors and windows just rectangular holes punched into the walls. His shop and apartment building known as the ‘Loos Haus’ has a cornice and columns, but the facades are otherwise undecorated. The Viennese called it ‘the house without eyebrows.’ The Emperor Franz Joseph was said to have taken detours to avoid having to look at it.

Loos was, on the other hand, no advocate of the simple life. The interiors of his houses, his shops and his American Bar are finished in luxurious sensuous materials – patterned hardwoods, marble and onyx – which provide decoration through their colours and textures. Loos admired English leather goods and men’s tailoring for the fact that they too combined plainness with luxury. A simple well-designed desk, he says, will last. A lady’s ball gown, ‘intended for only one night’, is a waste of the seamstresses’ time and the material used.

One might expect that Loos would have declared war in his lecture on the ornate neo-Baroque excesses of 19th century Austrian architecture and furnishings. Instead his main target is the practice of tattooing. Primitive men, Loos says, express the impulse to decorate by painting all their possessions including their own bodies. Children and criminals do the same.

“The Papuan tattoos his skin, his boat, his paddles, in short everything he can lay his hands on. He is not a criminal. The modern man who tattoos himself is either a criminal or a degenerate. There are prisons in which eighty per cent of the inmates show tattoos. The tattooed who are not in prison are latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If someone who is tattooed dies at liberty, it means he has died a few years before committing a murder… The urge to ornament one’s face and everything within reach is the start of plastic art. It is the baby talk of painting.”

Where do these ideas come from? Why is Loos so exercised about people decorating their bodies? He has been reading the work of Cesare Lombroso, the Italian pioneer of ‘scientific’ criminology. Lombroso subscribed to the theory, widely held among late 19th century biologists, that ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’, or in slightly plainer language, that an animal in the process of development from embryo to adulthood goes through the same series of (adult) forms as the evolution of the species. Evolutionary history is recapitulated in the growth of each individual. In Loos’s own erratically biological and psychological account: “When man is born, his sensory impressions are like those of a newborn puppy. His childhood takes him through all the metamorphoses of human history. At two he sees with the eyes of a Papuan, at four with those of an ancient Teuton, at six with those of Socrates, at eight with those of Voltaire.”

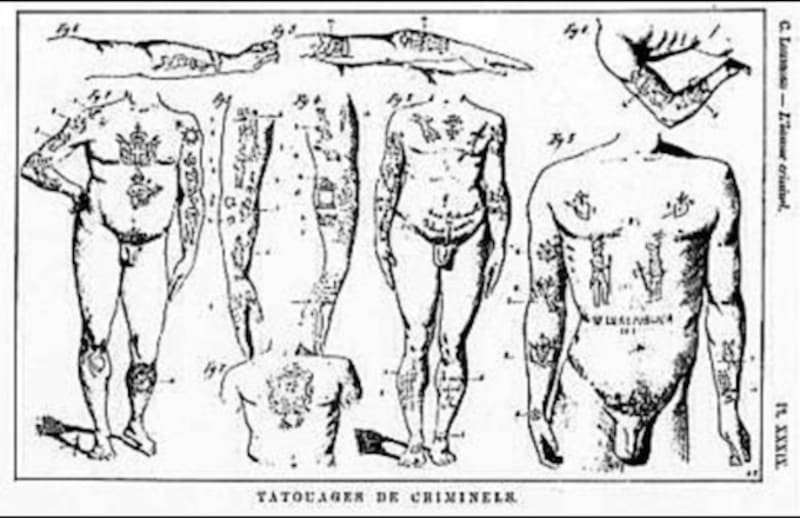

However, some humans never reach the higher stages of evolution and civilisation: these are congenital criminals. The criminal can be recognised by distinctive characteristics of face and body. Lombroso spent much time gathering statistics, measuring heads and bodies and collecting mug shots. Among other giveaway habits, criminals have a propensity for acquiring tattoos, many of them messages proclaiming their defiance of society and the law: ‘Friends of the contrary’, ‘Vengeance’, ‘Son of disgrace’. One French convict carried the slogan ‘Vive la France et pommes frites!’ on his person. Because criminals are evolutionary throwbacks they resemble ‘savages’ or children, other classes of human who are incompletely developed, morally backward, and enjoy painting themselves. “Tattooing is, in fact, one of the essential characteristics of primitive man, and of men who still live in the savage state.”

In an article on ‘The savage origin of tattooing’ published in 1896 Lombroso makes the same links to modern dress styles as Loos. “Simplicity in ornamentation and clothing and uniformity are an advance gained during these late centuries by the virile sex, by men, and constitutes a superiority in him over woman, who has to spend for her dress an enormous amount of time and money, without gaining any real advantage, even to her beauty.”

Lombroso’s racist and sexist pseudo-science was greatly influential on the emerging discipline of criminology, on police work, and on sentencing practice up to World War I and beyond. As for the influence of Loos’s lecture: it was printed in a number of places, including Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant’s magazine L’Esprit Nouveau in 1920, with an introduction claiming Loos as “one of the predecessors of the new spirit.” Loos certainly anticipated the white ‘cubist’ modernism of Corbusier and the later Bauhaus. But the evolution of architectural culture did not remove decorative elements from the work of all modernists as Loos hoped: witness the ‘organic’ ornament of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, or the geometric murals of the De Stijl architects in Holland.

Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays, ed. Adolf Opel, Ariadne Press, Riverside California 1998

Cesare Lombroso, ‘The savage origin of tattooing’, Popular Science Monthly, Vol.48, April 1896