Painting the laundry boats: by Murray Fraser

A guest article from Murray Fraser, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London

Boats sail on water. Water is required aplenty for washing clothes. What could be more obvious, and indeed practical, than a laundry boat? Able to pump in river water and sluice out the dirty waste, there had been many examples throughout Europe since medieval times. The breakthrough came with steam-powered washing machines, providing a commercially successful solution to help deal with public demand in rapidly growing cities such as Paris, Walter Benjamin’s ‘Capital of the 19th Century’.

Far less obvious, however, is the link between laundry boats and painting, two phenomena that might well seem antithetical.

In fact, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries a fair few people in France spent hours depicting laundry boats by the application of oil paint (more robust than watercolours!) onto stretched canvas sheets. Social Realism formed a strong strand within French art and literature of the period, and one can certainly see the attraction of laundry boats as a subject. As part of the busy river traffic, these boats were crewed by ordinary working folk engaged in one of the most humdrum of everyday tasks. It was positively Zola-esque.

Laundry boats became a bit of a craze among the French Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and Fauves. Auguste Renoir painted ‘Laundry Boat by the banks of the Seine, near Paris’ around 1872–73; Alfred Sisley painted ‘The Loing at Moret, the Laundry Boat’ in 1890; Maurice de Vlaminck the ‘Laundry Boat at Chatou’ in 1908; and so on. Visiting artists also got in on the act, including Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Laundry Boat on the Seine at Asnières’, 1887, painted while living in Paris for two years with his art dealer brother, Theo. The boat depicted was owned by Monsieur Lebreton and moored near the Pont de Clichy.

Most solemn of all was ‘Le Douanier’, Henri Rousseau – the quintessential ‘Sunday painter’ famous for imaginary jungle scenes, and also creator of ‘The Laundry Boat of the Pont de Chareton’ in* *1895. With a mood more reminiscent of a steamboat heading up the Zambezi, the chimneys on his boat echo those of flour mills and factories on the river’s banks, while his trees rise up like green plumes of smoke. From around 1900 there was even a factory-cum-studio in Montmartre nicknamed ‘Le Bateau-lavoir’ which formed a crucible for Modernist art and poetry just prior to the First World War. The rickety building was so-called, because in windy weather it rocked and groaned, like a river boat. It served as the communal working space (‘The Central Laboratory for Painting’) for Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Amedeo Modigliani, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob and others. In 1908 these artists and poets – prompted by Picasso and Apollinaire – hosted a legendary celebratory banquet at ‘Le Bateau-lavoir’ for Henri Rousseau, thereby cementing the latter’s reputation a decade or so after having painted an actual laundry boat at Pont de Chareton.

It is a stirring tale, another triumph of art as a mimetic practice. There is, however, only one person who ever decided to reverse the process and paint a real-life laundry boat to imitate a work of art – in his case, to express an architectural theory. He was Gottfried Semper.

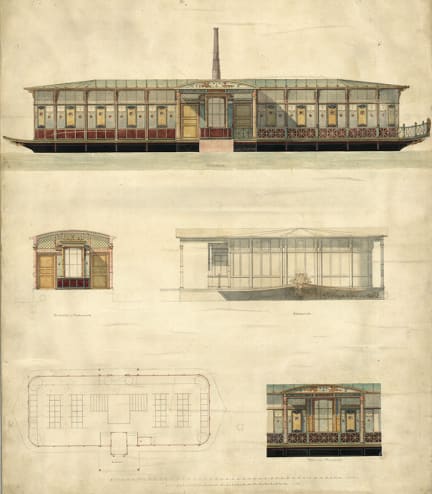

Semper was born in Altona, now part of Hamburg, in 1803 and became undoubtedly one of the most important German architects/theorists of the 19th century. His eventful life and wide-ranging interest in arts, crafts, weapons and architecture saw him design some genuinely prestigious buildings – notably the Hoftheater in Dresden of 1841, destroyed by fire in 1869 and rebuilt as the Semperoper – plus some rather curious commissions on the side. As a Saxon republican, the barricades he designed for the 1848 Rising in Dresden were so difficult to break down that they resulted in an arrest warrant being issued by the King of Prussia; while in exile in London, Semper not only designed several displays for the 1851 Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace, but also the gaudy catalfaque for the Duke of Wellington’s funeral in November 1852. In between such tasks Semper wrote brilliant theoretical texts about the cultural and technological origins of architecture, including his unfinished 1860s masterpiece, Der Stil in der technischen und tektonischen Künsten [Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts]. None of his various side-projects were so curious as his scheme for the Treichler laundry ship on Lake Zurich, conceived between 1861–64 for a Swiss entrepreneur.

To understand Gottfried Semper’s design, it is necessary to dig into his somewhat complex theoretical system. One of his key intellectual aims throughout his life was to prove that the marble temples of Greek antiquity had not been left white but were painted in very bright colours – which for Semper harked back to the practice of early human cultures in creating their interior spaces by wrapping mobile, demountable wooden frames with woven, patterned textiles. Semper was not the first to argue that Greek temples had been painted, and it remained a somewhat contentious subject in the mid-decades of the 19th century: the dispute between Semper and the renowned German art historian, Franz Kugler, was the stuff of legend in terms of academic feuds, ended only by Kugler’s death in 1858. Kugler was defending a tradition – which Semper was openly attacking – that dated back to the founding figure of German art history, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose seminal 1764 book on *The History of Ancient Art *had praised the Greeks for their austere, white Classicism, which he and his later acolytes felt was unsurpassed in human history.

Semper too thought that Greek temples were beautiful, but for him the crucial process was that the ancient Greeks had gone on to paint their stonework to turn it into something truly sublime – thereby transcending its mere materiality to express the highest possible human ideals. When it came to a laundry boat on Lake Zurich, physics and economics meant that marble was out. Instead it was built of a profiled iron frame covered with timber and iron sheets, emulating the latest boat-building technology as used by the ‘iron-clads’ in the American Civil War (1861–65). After all, the saga of the day-long, cat-and-mouse skirmish between the Union’s *Monitor *and the Confederate’s *Merrimack/Virginia *had only recently gripped all those reading European newspapers. Semper could not possibly leave his ‘iron-clad’ untouched, and so its metal and timber surfaces were painted to give it the proper architectural ‘dressing’, thus hiding the sordid washing processes taking place within.

Semper’s laundry boat for Zurich – the city where he had moved to be head of the institution that later became ETH Zurich – was thus in essence a modern floating temple. Ptolemaic rulers in ancient Egypt had sailed around in huge floating palace-barges, called thalamegoi, designed like temples, and hence there were good historical precedents when it came to designing a 19th century laundry boat. It might even have been designed in Greek Revival style if Semper did not happen to disagree with Winckelmann’s polemic. Instead, he believed that Neo-Renaissance was the only relevant style for the times. The only real giveaway in Semper’s Italianate scheme was a rather tall central chimney that he drew clearly enough in his rendering of the boat’s front elevation, yet conveniently omitted from the other drawings lest it look too odd.

Michael Gnehm vividly encapsulates Semper’s project in an entry for the new edition of Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture:

“With the remarkable Laundry Ship that he designed for Heinrich Treichler, a boat-builder in Wädenswil on Lake Zurich, he realised his only architectural project to have its external walls entirely painted. The result was a fascinating combination of contemporary industrial technology and older art history: a ship having the low shape of an Italian Renaissance pavilion with central portal on its longitudinal side, looking like the bath pavilions that Semper also designed. The ship was built with external metal sheets (internally covered with wood), and the block accentuated by a central, candelabra-like chimney connected to the boiler. This techno-artistic combination found further expression in the slender columns and cast-iron consoles, the latter having the shape of women, while the painting scheme of the ship’s external walls adapted the polychrome wall decorations of ancient Pompeian houses. The Laundry Ship was docked in the River Limmat in Zurich’s city centre, and performed its washing service there for eight years until 1872, when it was removed to Wädenswil to be repurposed as a workspace. It was destroyed only in 1960.”

No artist is recorded ever having painted a depiction of Gottfried Semper’s laundry boat. He should have designed it for Paris.

Eva Branscome, Murray Fraser and Michael Gnehm, ‘Central Europe (Germany and Austro-Hungarian Empire), 1815–1914’. In Murray Fraser (ed.), Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture (Vol.2). Bloomsbury: London, 2020, pp. 512–558

Martin Fröhlich, Gottfried Semper: Zeichnerischer Nachlass an der ETH Zurich: Kritischer Katalog, Birkhauser: Basel, 1974/1991

Michael (Mikesch) Muecke, ‘Mobile Foundations: A Reading of Complex Surfaces in Gottfried Semper’s Treichler Laundry Ship’, Aurora, the Journal of the History of Art, vol.2 no.2, 2001, pp. 54–88