Quarter-detached

The familiar names for house types distinguish the ways in which they are attached - or not - to neighbouring houses: detached, semi-detached (in pairs), terraced (in rows). But there is another possible configuration that is found only rarely, and for that reason has no standard designation, where houses are grouped together in fours. We might call these ‘quarter-detached’.

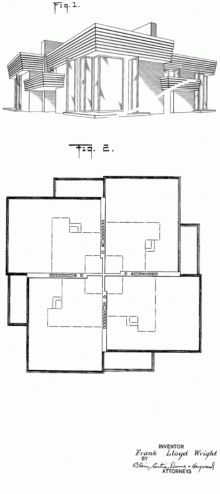

Some houses were built in this arrangement for workers in cities in the north of England in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were called ‘cluster houses’ or sometimes ‘back-to-backs’ but were indeed combined in fours. The earliest surviving example, dating from 1792, is at Darley Abbey in Derbyshire, and is known as ‘The Four Houses’. Some had gardens but others, like this example in Keighley, Yorkshire, had no outdoor space. Frank Lloyd Wright designed a scheme in 1938 known as the Ardmore Experiment in Pennsylvania – otherwise Suntop Homes – with four of his ‘Usonian’ houses in a pinwheel plan. The rooftop terraces and gardens were enjoyed by the occupants, but the design was technically not a complete success. Two of the houses burned down – possibly because the garages adjoined the boiler rooms - and have been rebuilt.

What must be the largest development of quarter-detached housing ever built is in the industrial city of Mulhouse in eastern France. This was an initiative led, with other philanthropists, by Jean Dolfuss, owner of the Dolfuss-Mieg and Company textile factory. It has become known as the Cité Ouvrière. Construction began in 1853 and continued up to 1897 by which time 1243 houses had been completed. There are conventional back-to-backs, terraced houses and semi-detached houses, but the majority are quarter-detached. Two or more groups of four houses were set on each block, with narrow alleys running between. There was space for small gardens on all sides of each group.

The inventor of this Carré Mulhousien – the Mulhouse square block – was émile Müller who later opened a factory of his own, making architectural ceramics. It was Müller who designed the decorative tiles for the facades of the Meunier chocolate factory at Noisiel, famous among historians of construction as one of the first buildings with a complete iron skeleton for both floors and walls.

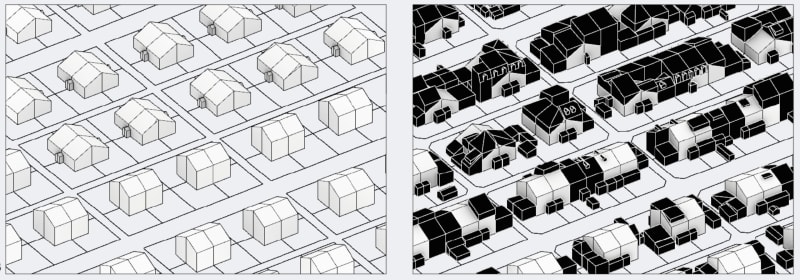

The occupants of the Cité Ouvrière were able from the start to save towards owning their houses, by paying monthly instalments over fifteen years. Once they were in possession they embarked on all kinds of improvements and alterations. Houses were extended sideways and upwards; pairs of houses were joined together; and houses were sold or rented as shops and workshops. Fani Kostourou has studied these changes in detail and has made a classification. Because each house had two facades with land in front, it could be built out in these two directions. It could also be extended upwards by converting the attic, or putting on another storey. Porches and sheds could be added. The bird’s eye view of parts of the Cité, drawn by Kostourou, shows the situation ‘before and after’, that is to say the original design, and the present state. All extensions and changes are shown in black in the ‘after’ view.

Judging by the evident enthusiasm with which the owners have modified their houses, the Cité Ouvrière has been a great success in terms of adaptability – although the original houses were small, so that no doubt created pressure for change. But if quarter-detached houses with gardens on this model have proved popular at Mulhouse, why has the type not been more widely adopted?

One basic problem with any quarter-detached arrangement is that it is impossible to provide ventilation through the house from back to front. This was the reason why these and all other back-to-back houses were eventually banned in Britain. There are also issues of privacy, although no worse than in terrace houses.

The English examples, and the Cité Ouvrière, were built for industrial workers, at a time when all were expected to walk to the mills and factories. The alleyways at Mulhouse are sized for walkers, and as a result are barely the width of one car. The gardens on the corners have been chamfered so that cars can just turn. The blocks are thin, meaning that the alleys despite being narrow take up a significant proportion of the land area. Had the alleys all been two-way roads, then perhaps as much as a third of the total area would have been under tarmac. This is a general problem with small urban blocks in the age of the car. One notable example is Portland Oregon, laid out in small blocks, where 45% of the land in the centre of the city is covered by streets, and blocks have been joined together and streets closed to gain more space for buildings.

But perhaps the over-riding reason for the disappearance of the quarter-detached type of house, is that – by definition – it can have no back garden. Wright’s Suntop Homes had to share a communal garden. Terrace houses by contrast can have both front gardens and secluded back gardens, as large as the price of land will allow. This I suggest is why we find so many terraced houses in the denser parts of cities, and so few quarter-detached.

Special thanks to Fani Kostourou

Fani Kostourou and Sophia Psarra, ‘Formal adaptability: a discussion of morphological changes and their impact on density in low-rise mass housing’, Proceedings of the 11th Space Syntax Symposium, Lisbon 2017: www.11ssslisbon.pt

Fani Kostourou, Adaptability of the Urban Form: Mapping Changes Over Time and Across Scales in the Cité Ouvrière of Mulhouse, PhD thesis, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London 2020