Roger Rabbit and the Red Cars

The movie ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’ is set in Los Angeles in 1947. The wicked Judge Doom has bought Toontown – which is of course Hollywood – and is planning to demolish it. In a key sequence, Doom confronts Roger and shows him a terrifying vehicle whose tanks are filled with a liquid that the characters refer to in horror as ‘dip’. This is acetone, which dissolves celluloid, and is therefore fatal to Toons. Doom’s plan is to build a monstrous eight-lane superhighway through Toontown and develop the land alongside. But the Toons, with the help of Eddie Valiant – the detective played by Bob Hoskins – are resisting. As Eddie says: “Who would want to drive the freeway when they could take the Red Car for a nickel?”

The film builds on a widely-circulated story about the history of LA. From the 1890s, property developers began constructing ‘interurban’ railways to connect the scattered small townships that were spread across what is now greater Los Angeles. In the first decade of the 20th century, Henry Huntington bought out more than seventy of these companies and consolidated them into a single network, the Pacific Electric Railroad. The trains were known affectionately as the Big Red Cars. They connected Santa Monica, Glendale, Long Beach and Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles, and gave access for tourists to the sea and the mountains. The standard fare was 5 cents. At the peak it was the biggest electric railway system in the world, with a network extending over some 1100 miles. Several scenes in ‘Roger Rabbit’ are set in a bar with a large map of the network on the wall. The Pacific Electric went into decline in the 1930s. It revived a little after World War II but ceased operation in the 1950s, and today almost all trace, and all the track, has disappeared.

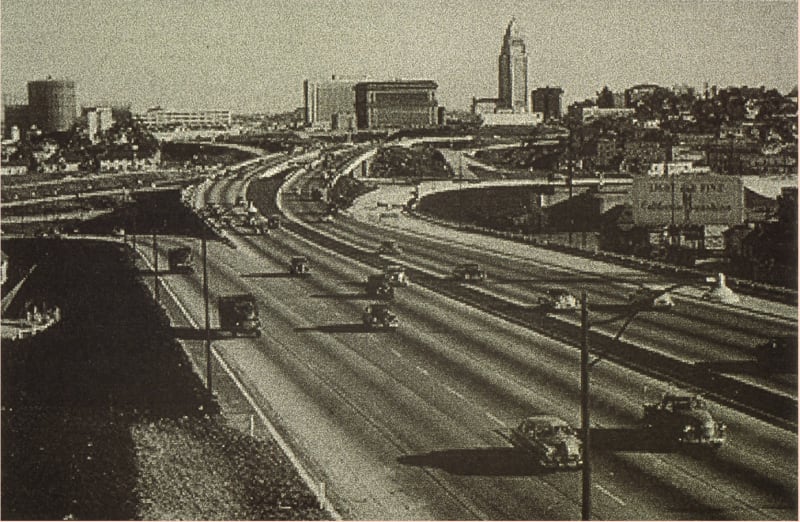

The story goes that this early and highly successful public transport service was sabotaged by financial interests connect to the automobile industry. Judge Doom is their representative in ‘Roger Rabbit’. Some short sections of motorway were constructed in the 1940s. But the first route to be built after the War was indeed the Hollywood Freeway. In many places the freeways were laid over the old railway lines, which literally paved the way for the car.

It’s an attractive story for conspiracy theorists, but is largely a myth. The Pacific Electric system was a spiderweb of routes, with large areas of empty land in the interstices. Its customers were concentrated in the towns at the nodes. California was the place where, from the 1910s, car ownership grew first and fastest in the United States. Once sufficient numbers of people had cars, developers could build houses for them at low densities in these suburban neighbourhoods, which were not accessible using the Red Cars. Meanwhile downtown Los Angeles, not built for automobiles, became choked with traffic as early as 1920. Department stores started to move to the suburbs, and they and the newly-invented supermarkets could only be reached by road. The City of Los Angeles debated keeping the centre accessible by rail with elevated lines or tunnels, but these were rejected as too expensive, and only one mile-long tunnel was built, connecting a line from the north of the city into a terminal below Hill Street. (Both tunnel and underground station still exist, the last vestiges of the Pacific Electric. The station is disused, apart from the filming of an occasional episode of ‘X-files’.)

In 1974 an American government analyst called Bradford Snell presented a report to the US Senate, in which he argued that public transport in America had been deliberately destroyed by the automobile industry, and specifically by the car manufacturers General Motors. “Nowhere’, Snell said, “was the ruin from GM’s motorization program more apparent than in Southern California.” General Motors and other car interests had, according to Snell, bought up the Pacific Electric and dismantled it, in order to sell automobiles. This account continues to be told in books and documentary films. It forms the basis of the plot of ‘Roger Rabbit’.

It is true that a company in which General Motors had a shareholding, together with various oil interests, bought up a separate streetcar system in downtown Los Angeles 1944, and dismantled it. But they replaced *the trams with diesel buses, which GM manufactured. GM’s interest was in road transport certainly, but it was in *public transport on the roads. Buses were being introduced on many routes before the War because they were more flexible than trains, and could help to slow the decline of the public transit system as a whole. The old Pacific Electric, so far from providing an effective and popular service, had been losing money and riders for years. Angelenos took enthusiastically to their cars, and were very keen from the beginning about the freeways. If Eddie Valiant wanted to be historically accurate, what he should have said was “Who would pay a nickel to ride the Big Red Cars, when they could drive the freeways for free!”

‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’ still ends happily. Roger manages to thwart Judge Doom’s scheme, and the Toons all escape back to Toontown through a railway tunnel. This is the real old tunnel out of the Hill Street terminal, on the line to Hollywood.

Spencer Crump, Ride the Big Red Cars: How Trolleys Helped Build Southern California, Trans-Anglo Books, Los Angeles, 1970

Bradford Snell, American ground transport: a proposal for restructuring the automobile, truck, bus and rail industries, U S Government Print Office, Washington DC 1974