Schinkel's panorama

Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Germany’s greatest neo-classical architect, trained for the profession at the start of the 19th century, and toured France and Italy studying buildings and making drawings. He came back to Berlin in 1805, but the following year Napoleon defeated the Prussians, the French occupied the city, and all construction work came to a halt. Schinkel turned to painting, by which he made his living for the next ten years. Through his friend Karl Wilhelm Gropius, a set designer, he met Karl’s father Wilhelm Ernst Gropius who ran a company making theatrical masks, and who organised exhibitions of paintings every year at Christmas. (Art and architecture ran in the family: Wilhelm Ernst’s brother was the great-grandfather of Walter Gropius.)

Schinkel helped Wilhelm Ernst with backdrops for his puppet theatres, designed special window displays for shops, and made backgrounds for nativity scenes. He exhibited his own pictures, based on sketches made on his tour, beginning with a painting of the Milvian Bridge in Rome. He started to experiment with ‘deceptive illusory images’, first in the lodgings that he shared with Karl Wilhelm, and then in a larger space in the royal stables. These were paintings made on translucent material, illuminated from behind, to create effects of changing light and motion. *The Fire of Moscow *of 1812 recreated the conflagration set by the inhabitants retreating in the face of Napoleon’s advance earlier that same year. It seems that Schinkel was able to simulate the flames and suggest the movements of the fleeing crowds. These entertainments sound very like the ‘dioramas’ introduced by the painter and pioneer photographer Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in Paris, just ten years later.

Schinkel had visited Paris at the end of his European tour, where he saw one of the panoramas painted by Pierre Prévost. Panoramas were giant cylindrical paintings of cities, landscapes, or battle scenes, seen from elevated viewpoints, displayed in special circular buildings of a type invented by Robert Barker in London in the 1790s. The figure below shows a cross-section of Barker’s rotunda in Leicester Square. Patrons climbed stairs to two central viewing platforms, the one above for a second picture of smaller diameter. (Other later buildings displayed just one painting.) The illumination came from rooflights.

In a panorama building, a number of factors contribute to make the illusion particularly powerful. Viewers cannot see the edges of the picture, so they cannot determine how far away it is. They are sufficiently distant from the picture that they cannot make out the brushwork or texture of the canvas. And they are constrained in position, which minimises the effects of parallax. If a person looks at a real scene and moves sideways, objects at different distances appear to move relative to each other. This is parallax. In a normal painting hung on a wall, parallax effects do not occur when the viewer moves, so it is easy to see that the image is painted on a flat surface. In a panorama by contrast, the fact that the audience cannot move about, and the fact that the picture shows mostly objects in the far distance, means that significant effects of parallax would not be expected if the scene was real: so the viewers are more effectively taken in by the painted deception.

Prévost painted the first panoramas ever displayed in Paris, shown in two rotundas on the Boulevard Montmartre, starting in 1799 with a View of Paris from the Tuileries. Perhaps Schinkel saw Prévost’s View of Amsterdam, on exhibition in 1804. While working on his other ‘deceptive illusory images’, Schinkel conceived the idea of painting a panorama of his own, based on sketches he had made in Palermo in Sicily. He got permission to use a space at the Berlin opera house, and spent four months working madly, plagued by headaches and hardly sparing time to eat. He showed the finished work in a temporary rotunda, nine metres in diameter, on St Hedwig’s Square. It was a great success and remained on show for several years. Eventually Schinkel sold the painting to Wilhelm Gropius, who took it on a tour of other German cities. Its ultimate fate is not known. According to one account it was bought by a rich Italian for his Neapolitan villa.

Shortly before his death Schinkel asked Karl Gropius if he would organise the repainting of the Palermo panorama on a larger scale. Gropius fulfilled his friend’s wish, and had a version made for a special building with a diameter of 21 metres, opened in 1844. There was a cunning lighting system that could simulate the transition from full daylight to moonrise. This painting was lost in a fire in St Petersburg, where it was on tour.

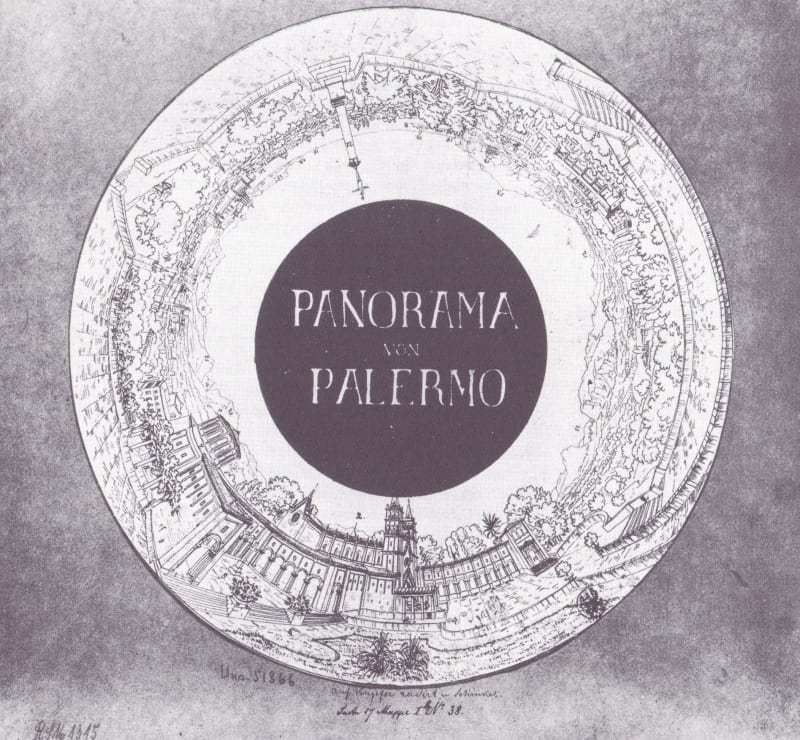

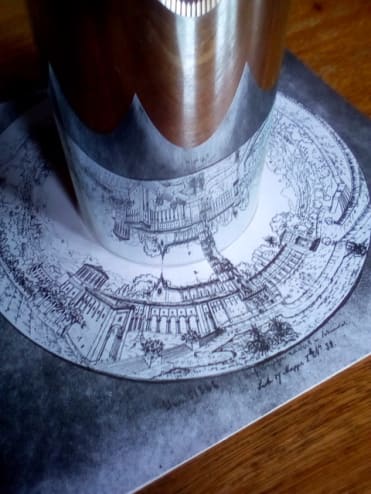

For his first show in Berlin, Schinkel made a small drawing of the Palermo scene in flat circular format, which was printed as an advertisement, guide, and souvenir. In the centre of the drawing was a black circle. Other panoramas advertised themselves with similar cards. It was difficult obviously to print a reproduction of the cylindrical panorama itself on a flat sheet, other than on a very long strip. The circular format served to give an impression of the picture in the round: one placed a cylindrical mirror on the black circle, and saw an upright version reflected on the mirror’s surface, facing outwards instead of inwards. The ring-shaped drawing was an *anamorphic projection *of the panorama, distorted when seen flat, but correct when seen in the mirror. This type of ‘cylindrical anamorphosis’ dates back to the early 17th century and was sometimes used to conceal erotic or politically subversive subjects. The photograph shows Schinkel’s view of Palermo in a curved mirror: but very oddly, he has got his picture upside down. Other examples of these circular advertising cards do not make this mistake.

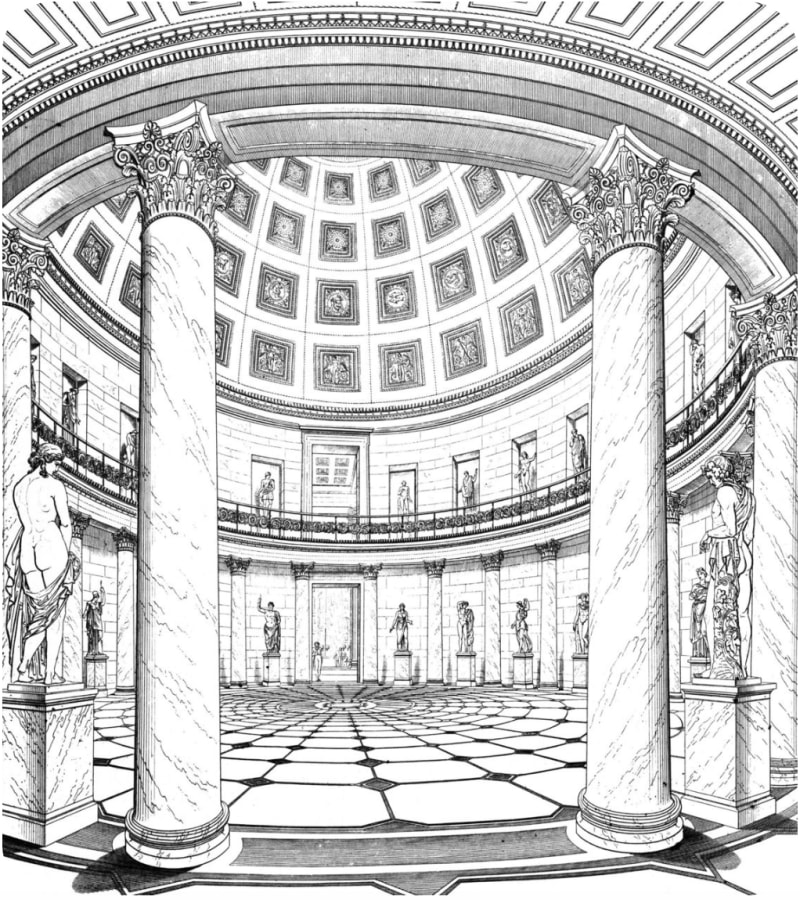

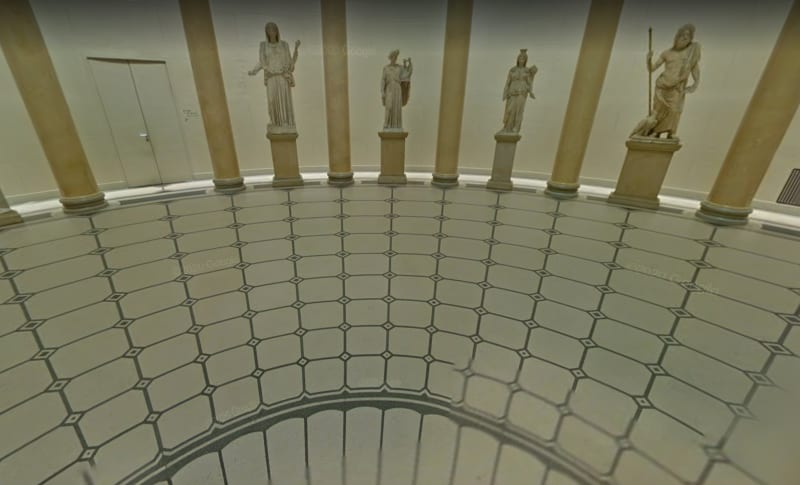

The architectural historian Emma Letizia Jones draws a comparison between the Palermo panorama and the circular domed hall at the heart of Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin. Here we find another example of what she refers to as the architect’s “love of sophistry and… deceptive possibilities.” The museum rotunda surrounds the visitor with real cylindrical architecture of course, not a painted illusion. The trickery comes in the floor. This is paved with a pattern of quadrilaterals, defined by straight lines radiating from the centre, and rings that are spaced wider apart, the further away they are from the centre. The pattern appears normal enough from most parts of the room. But when one moves to the very centre of the floor - marked by a black disc like the panorama advertisement - the quadrilaterals are suddenly seen as squares. The whole surface seems to tip upwards and inwards, and the viewer feels as though he or she is falling through the black hole. I have been to the Altes Museum, but sadly did not then know to test this phenomenon. But one can experience something of what it must feel like on Google Street View, which takes one to the very spot.

This is another kind of anamorphic illusion. The Dutch artist Jan Dibbets illustrated the principle in the 1960s in a very simple and striking work. Dibbets laid out a trapezium in white tape on a lawn. The shape was designed to appear as an exact square when seen or photographed from a particular viewpoint. The mind prefers to see a square rather than a trapezium, so the grass inside the tape outline seems as a result to stand up vertically, and the ‘square’ appears to be graduated in texture from bottom to top. The tiles in the Altes Museum do the same, apparently changing from horizontal trapezia to vertical squares, surrounding the poor museum visitor with an illusory cylindrical ‘panorama’. Did Schinkel arrive fortuitously at this effect; or did he know exactly what he was doing?

Bernard Comment, The Painted Panorama, Harry N Abrams, New York 2000

Stephen Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium, Zone Books, New York 1997

Emma Letizia Jones, ‘The wanderer’, AA Files, Architectural Association London, No.72, 2016 pp.152-160