The Arch of Constantine in a French garden

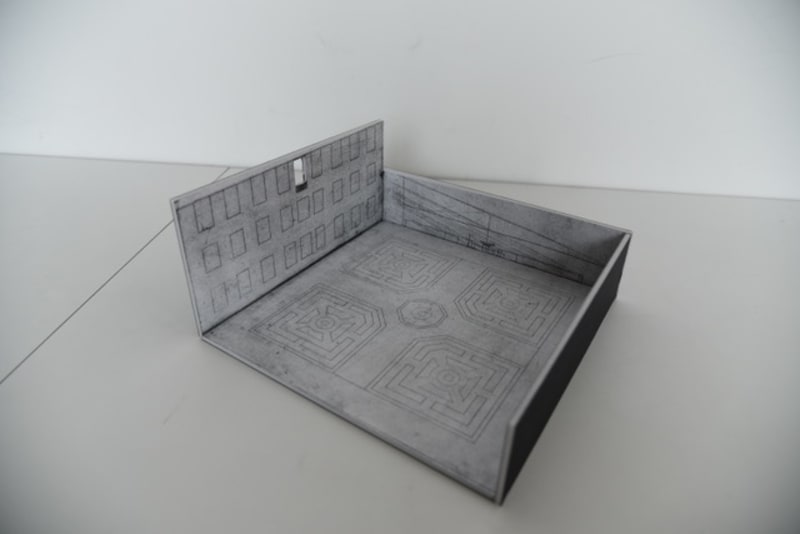

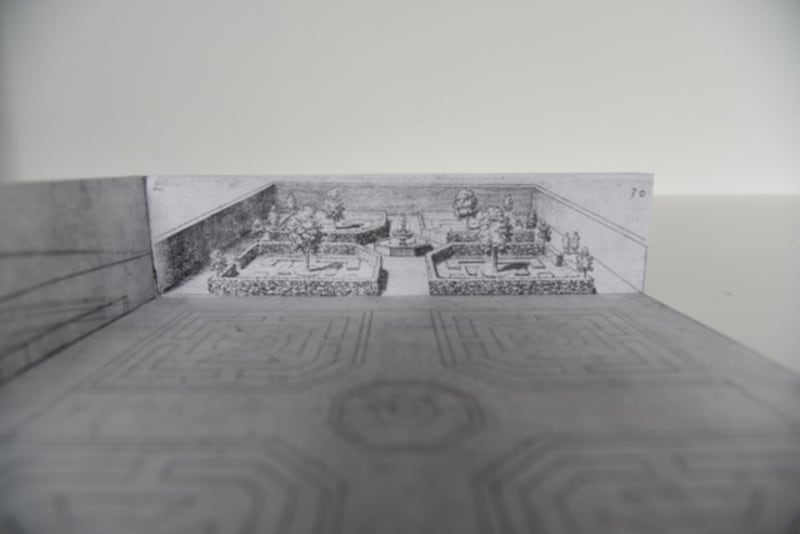

In France in the mid-17th century there was a fashion for installing large illusionistic paintings in gardens. These were positioned, and their perspectives carefully calculated, so as to give the impression that the spaces of the gardens continued beyond their actual boundaries. Salomon de Caus was a French designer of gardens and fountains who also wrote a book on perspective. In it he gives instructions for producing a picture of this kind, with an explanatory diagram. A real garden with four parterres and an octagonal fountain adjoins the front of a house. De Caus shows this garden in plan view, drawn on a page with paper flaps glued on three sides, which can be folded up to make the walls of house and garden. The bottom flap represents the façade of the house. The top flap represents the far wall of the garden, on which is painted a perspective of an imaginary garden beyond.

Gregorio Astengo has folded up the flaps and has taken a photograph from the theoretical viewpoint for which the perspective is calculated: an upper window of the house (shown hatched in the drawing). This demonstrates the illusion: the painted garden on the wall seems to continue the actual space. In this case the *trompe l’oeil *picture is an exact copy of the real garden, and the space is doubled; but clearly there could be other possibilities.

The English traveller and gardener John Evelyn saw several of these French paintings. He describes one in his *Diary *for March 1644. This was at the Comte de Liancourt’s house in the rue de Seine in Paris. “Towards his study and bedchamber joins a little garden, which, though very narrow, by the addition of a well-painted perspective, is to appearance greatly enlarged; to this there is another part, supported by arches in which runs a stream of water, rising in the aviary, out of a statue, and seeming to flow for some miles, by being artificially continued in the painting, when it sinks down at the wall.” The picture was by Jean Lemaire who worked closely with the painter Nicolas Poussin and specialised in landscapes and antique architecture.

Evelyn mentions – although does not identify – another such picture in his great book on gardening, the Elysium Brittanicum. This was at “at the extreme of an ample walk”, where sky and clouds were painted on a high wall. In front of this was another wall of the same height, decorated with a perspective picture of ‘Ruins of a Roman Antiquitie’. The front wall was pierced with real openings within window frames and arches depicted in the painted architecture. As one walked past, the painted clouds beyond seemed to fly past these openings.

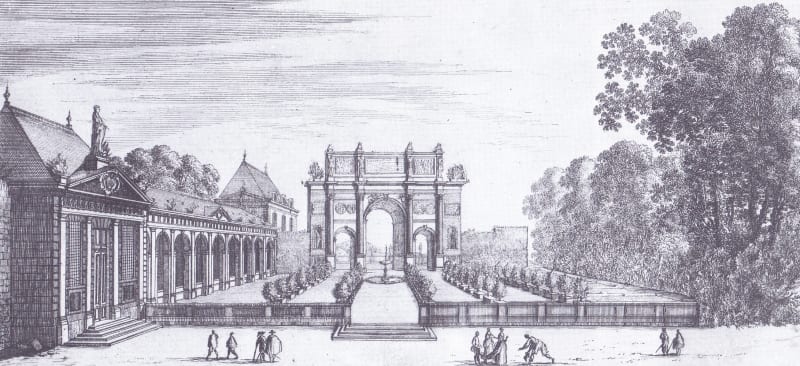

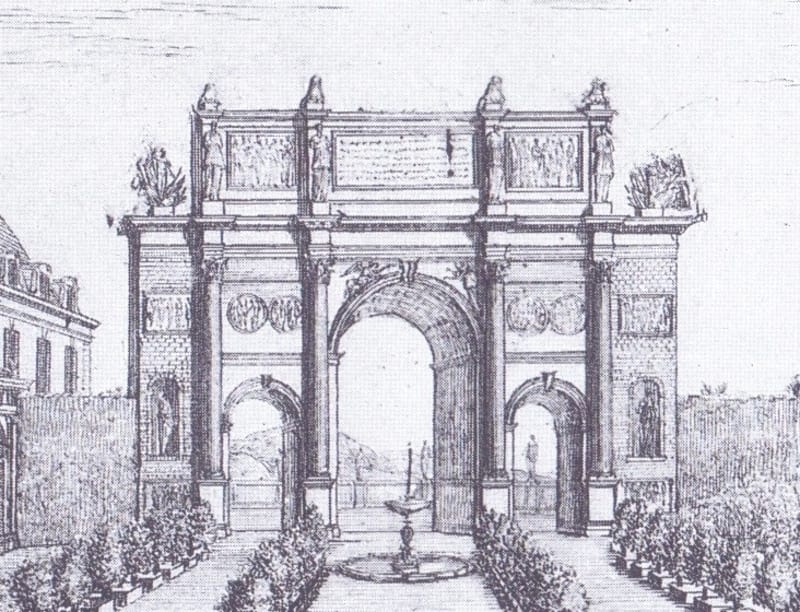

The largest and most spectacular of these *trompe l’oeil *works was a full-sized painting of the Arch of Constantine in Rome, again by Jean Lemaire. This was installed in the lavish gardens of Cardinal Richelieu’s chêteau at Rueil near Paris, laid out in the 1630s and filled with entertainments of many kinds. The Arch appears in an engraving by Israël Silvestre.

Here the purpose was rather different: to simulate a building in a garden, rather than extend a view. The shallow supporting structure was shaped to follow the silhouette of the real Arch, with a painted sky and distant landscape visible through the openings. Evelyn visited the garden and was “infinitely taken with this agreeable cheat.” The work was so well done, he says, “that even a man skilled in painting, may mistake it for stone and sculpture.” Swallows, “thinking to fly through, have dashed themselves against the wall.” Later visitors to Rueil made similar observations. Lodewijck Huygens in 1665 said that birds tried and failed to perch on the Arch’s cornices.

Evelyn might have been impressed by the Arch, and we can imagine from Lemaire’s conventional landscape canvases that his treatment of materials and lighting would have been highly realistic. élie Brackenhoffer, a visitor from Strasbourg, said that one could not be certain if the Arch was real or painted, before getting close enough to touch it. But there is an optical problem intrinsic to this kind of illusionistic perspective, which can be detected in Silvestre’s engraving.

Looking closely, we see that the painter Lemaire has taken a view of the Arch that is not central, but is from a point slightly to the left of centre. This is why we see the interior walls of the three archways on their right-hand sides, but not the walls on their left-hand sides. Silvestre has however chosen a different viewpoint for his engraving, in which the Arch is seen frontally, head-on. As a result, from this position Lemaire’s perspective illusion goes subtly wrong. In fact the deception would fail for *all *viewing positions other than Lemaire’s theoretical point of view: the further away from the true viewpoint, the worse the failure.

This dilemma vexed even the most skilful and knowledgeable of perspectivists*. *Baldassare Peruzzi’s painted illusions of columns and balconies at the Villa Chigi are completely convincing when viewed from the ‘correct’ eyepoints. But when one moves away from these positions, the deception is revealed. Lines that should properly continue straight become broken at the junction between the wall and the floor.

Salomon de Caus is aware of the difficulty. He recommends that garden perspectives be viewed by preference from specific constrained positions. His garden picture, as we saw, has its viewpoint in a second-floor window. The owner looking out from here over his grounds has the privileged ‘correct’ view. Any casual visitor wandering about at ground level, on the other hand, would see the lines of the imaginary garden failing to continue the lines of the real garden. If he was knowledgeable about perspective, he would see how and why his oeil *was not *trompé.

Salomon de Caus, La Perspective, avec la raison des ombres et miroirs, J Norton, London 1612 Chapter 25

Sabine Bouhedja ‘Perspectives en trompe-l’oeil et architectures feintes en Ile-de-France au XVIIe siècle”, in *Imaginaire et creation artistique à Paris sous l’ancien regime (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles): Art, politique, trompe-l’oeil, voyages, spectacles et jardins’ *ed Daniel Rabreau; Wiliam Blake, Bordeaux 1998 pp.63-76

John Evelyn, Diary, ed William Bray, Dent, London, revised edition 1952, Volume 1 pp.56-57

John Evelyn, Elysium Britannicum or the Royal Gardens, manuscript, British Library ADD MS 78342 p.159