The House of the Faraway Heart

Harold C Price founded a company in Bartlesville, Oklahoma that built oil and gas pipelines all over the world. On the recommendation of Bruce Goff, then Dean of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma, Price commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright in 1952 to design a high-rise office building for the firm.

Harold’s son Joe worked as an engineer on the construction of the Price Tower, and got to know Wright. One day they were in New York together, and Wright ducked into a bookshop to look at some prints. As Joe remembers: “There was a painting on the wall of great grape vines that was fascinating… You look at it and it does not look like a grape vine, but it feels like a grape vine. In my studies afterwards of that painting I realized that what the artist had done was leave out everything that wasn’t necessary and had left only the essence of a grape vine…” Price did not even know that the picture was Japanese. In fact, it was by Ito Jakuchu, one of the great masters of the Edo period (1615-1868). Wright was a connoisseur and collector of Japanese prints: this was the occasion when he passed on his enthusiasm to the young Price.

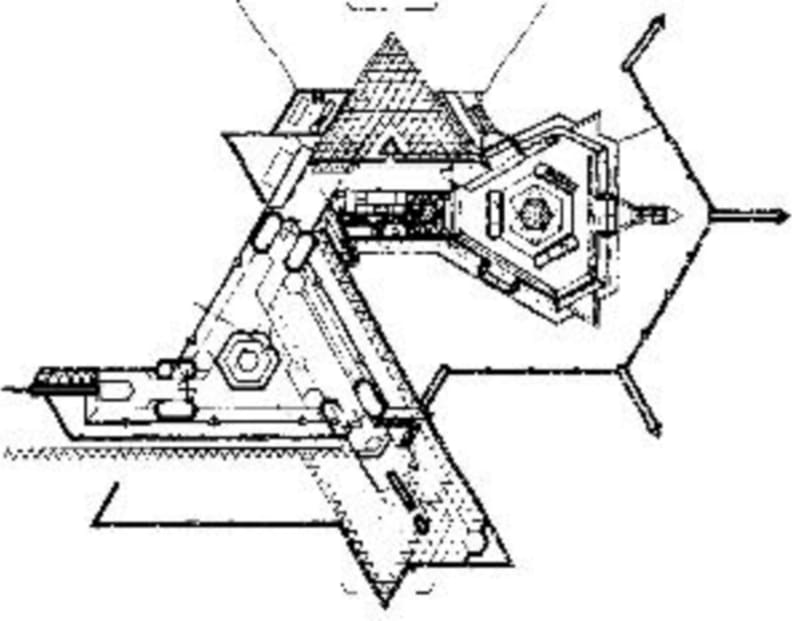

With a fortune inherited from the pipeline business, Joe Price built a studio house in 1958 on the family estate, designed by Bruce Goff. (Frank Lloyd Wright saw the drawings and was not entirely convinced. He said they were a ‘hopus-copus for an opus’.) The triangular structure was of gold anodised aluminium, supported on piers made of luminescent blue glass cullet and anthracite. Cullet is a waste product that forms in glass furnaces: Goff liked to use many kinds of scrap and found materials – although the budget for the Joe Price Studio was not exactly tight. Inside, the floor of the triangular central space was stepped to create luxurious bench seating, covered in deep white carpet. The ceiling was lined with goose feathers, and trailing streamers of cellophane hung like falling rain. There were small triangular bedrooms and a kitchen at the corners, with cabinets made from African zebra wood. The distinguished architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable described the house as “a *Playboy *dream, if *Playboy *were an architect.” In the 1970s the trees lining the approach road carried perfectly spherical golden fruit that on closer inspection turned out to be Christmas tree baubles.

Meanwhile Price was pursuing his obsession with Edo prints and screen paintings. He made several visits to Japan to meet potential sellers, and on one occasion hired an interpreter Etsuko Yoshimochi. They fell in love, married, and came back to start a family in Bartlesville. The Studio was clearly inadequate for this new phase in his life, and Price commissioned Goff to build an extension. This had a matching triangular geometrical discipline, but was realised in more sober materials. At the heart was a hexagonal gallery in which the prints were displayed, arranged in such a way that the viewer could see and contemplate just one work at a time. Outside there were Zen-like gardens with cullet in place of the raked sand. The Prices re-named the building Shin’enKan, or the ‘house of the faraway heart’.

Etsuko and Joe opened the house and gallery to visitors. Edo art had become unfashionable and undervalued in Japan, but the Prices revived its reputation and were among the world’s leading collectors. Eventually they donated 300 works to the Los Angeles Museum of Art, who erected a Pavilion for Japanese Art to house the collection. This building, also designed by Goff, was the architect’s last work, completed in 1988 after his death. The Prices moved to Corona del Mar in California, to a house designed by Goff’s pupil and former assistant Bart Prince, covered in a flowing rippling roof of wooden shingles in Prince’s signature manner.

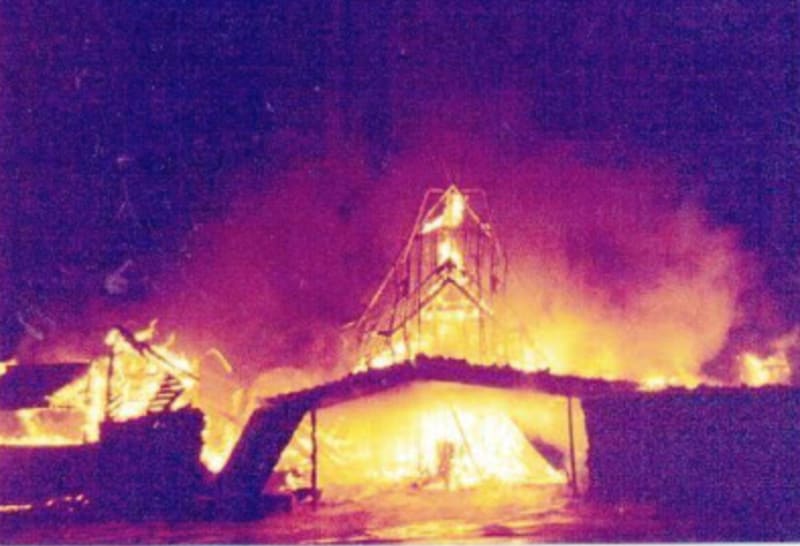

The Prices gave Shin’enKan to the University of Oklahoma who planned to use it as a Center for Creative Thought. One night in 1996 however the house was burned to the ground. A grand jury was convened in Oklahoma City two years later to investigate, but the arsonists have never been caught.

Mary Jo Nelson, ‘Shinenkan, the house that Price built’, The Oklahoman, 9th June 1985

Robert Morris, ‘The Hidden Side of Architect Rebel Bruce Goff’, PaperCity, 26th January 2019

Ada Louise Huxtable, On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change, Bloomsbury London 2010, p.300

Edan Corkill, ‘How an American Collector Brought Jakuchu to Tohoku’, *Japan Times *March 17th 2013