Buildings at the back: too high, too long

When a drawing or painting of an architectural interior or an urban scene is made accurately in perspective, it is possible to reconstruct the three-dimensional space depicted. This is done by a method of ‘reverse perspective’ - in effect working the standard rules of construction backwards.

When making a perspective image, one goes from a three-dimensional scene to a two-dimensional projection, relative to some specified eyepoint. Rays of light reflected off the scene meet at this eyepoint, passing on the way through the plane of the picture, where their positions are marked. In the technique of reverse perspective, these rays are followed in the opposite direction, from the eyepoint, through the relevant points in the picture plane, back into the scene.

The presence of tiled floors or pavements can be helpful for making measurements and locating the positions of buildings and figures on the ground plane. There can be ambiguities in the detail. But by applying common sense - that buildings are generally rectangular, walls are vertical, floors are flat, steps and doorways have typical dimensions, and so on - most of these ambiguities can be overcome, although a few may remain unresolvable. It was Leonardo, unsurprisingly, who first indicated how such a process could work.

Many perspective pictures have been subjected to this kind of analysis, either by hand, or since the 1980s using computer graphics - although human intelligence is still required. The activity tends to throw up surprises, even in the work of highly skilled artists. Buildings that look right in the picture can turn out to have strange geometries and may even be - in theory - floating freely in space.

Piero della Francesca’s ‘Flagellation of Christ’, painted probably in the late 1460s, provides an example. Since Piero was a mathematician and the most able theorist and practitioner of perspective of the fifteenth century, we would expect his construction of the classical portico in the foreground and the buildings in the distance to be rigorously consistent in their geometry; and so it turns out. B A R Carter and Rudolf Wittkower made an analysis in the 1950s and worked out the complex pattern of black and white tiles, seen at a very shallow angle in the picture.[1] In 1972 Marilyn Lavin published a reconstruction made by her and Thomas Czarnowski, including the whole of the very deep piazza as it extends into the far distance.[2] They also worked out how the space in which Christ is flogged is lit by a mysterious source of light - not the sun - located somewhere within the central row of columns.

I made a reconstruction for a television programme in 1992 and built a physical model some seven metres long.[3] In the photograph Martin Kemp (in the brown jacket) is pointing to the patterned floor tiles and I am working at the back. Our model included the two buildings at the right whose lower parts are hidden by two of the figures at the very front of the picture. This means that we do not know exactly where the buildings stand. They might be small and nearer to the viewpoint, or larger and further away. We made an arbitrary decision for the purposes of the model. But whatever the distance, these are tall thin towers, as the photograph of the model shows.

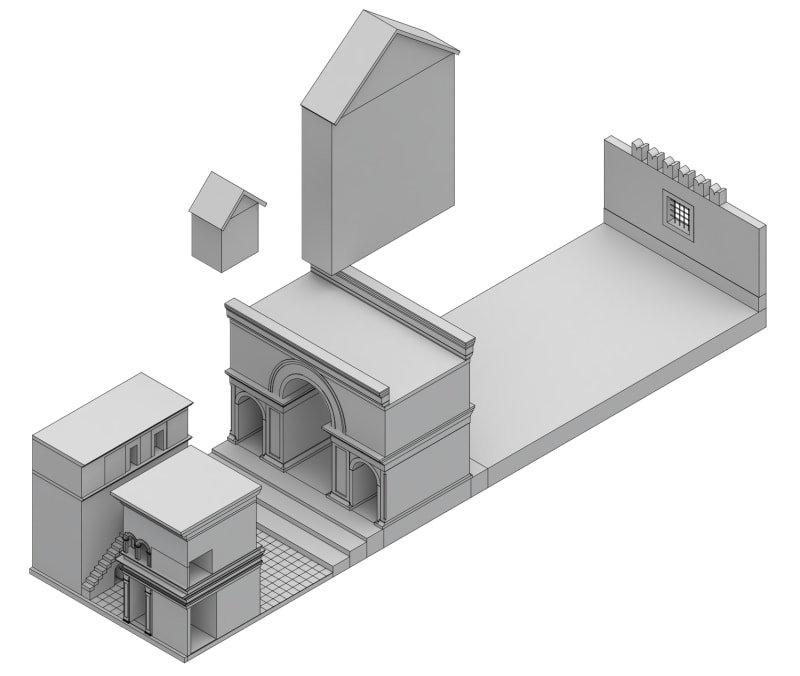

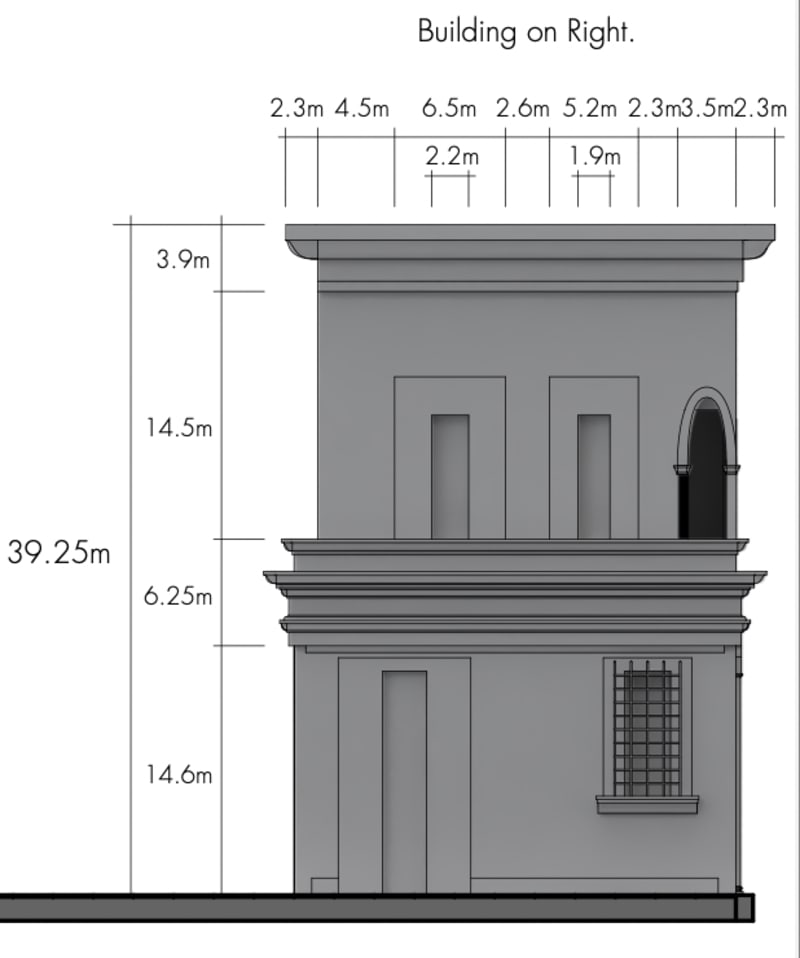

Something equivalent is to be found in Carlo Crivelli’s ‘The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius’, painted around 1486. As with ‘The Flagellation’, the ground surface is paved. I reconstructed the scene and buildings, and Martynas Kasiulevicius built a digital model. The Virgin sits in a room into which a golden ray of light, signifying the Holy Spirit, enters through a conveniently angled hole. This house and the building opposite with the external staircase are reasonably consistent and coherent in their perspective geometry, as is the triumphal arch in the middle distance, although viewers of the painting might by surprised to learn how deep it is - almost a tunnel.

At the top left of the picture, we see two houses. As with ‘The Flagellation’ we cannot see where these meet the ground. Their location and form are quite mysterious. Are these again very tall towers? Or do they stand on high ground that we do not see, on a level with the top of the archway? In the computer model we have left them floating unanchored in space.

I suggest that both Piero and Crivelli have not included these houses in the plan and elevation drawings from which they have constructed their complete perspectives. They have added the buildings at a later stage, to complete the compositions. They have adjusted the two-dimensional geometry to be perspectivally consistent with the remainder of the architecture.

Making the Crivelli model also turned up another minor finding. The side wall of the Virgin’s house is seen at a very steep angle. When seen in elevation the first-floor windows and arched balcony and the ground floor door turn out to be unrealistically thin. It is difficult for artists to judge the widths of features that are seen so obliquely, and to get them right in pictures. A small change in the position of a line in the painting can involve a large change in the depth of the feature represented.

A comparable problem is seen in very extreme form in a painting by Tintoretto, ‘Washing the Feet’, of 1548-49. Here by contrast, buildings become much too deep. In the background of this picture is a lake or canal lined by classical monuments, resembling a stage set of the kind pioneered by Baldassari Peruzzi and Sebastiano Serlio. This is closed on the far side, like the Crivelli, with a triumphal arch. Three ingenious researchers, Gianmario Guidarelli, Gabriella Liva, and Isabella Friso, have analysed this scene and made a digital model.[4] They find that the buildings around the near end of the lake have plausible geometries. But those further away, including the archway and a small temple to its right, are grossly distorted when reconstructed in three dimensions. Both are extremely long, and the arch is indeed a tunnel.

This is of course quite unimportant for the way in which we read the architecture, which looks perfectly plausible. The analysis suggests to me that Tintoretto, like Piero and Crivelli, has not extended his geometrical construction to these buildings, but has drawn their front elevations carefully and has improvised the return facades (very inaccurately) by eye.

I am grateful to Gianmario Guidarelli for permission to reproduce the images of the Tintoretto model, which was built by Gabriella Liva.

- R Wittkower and B A R Carter, ‘The Perspective of Piero della Francesca’s ‘Flagellation’’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol 16 No 3/4, 1953 pp.292-302

- Marilyn Lavin, Piero della Francesca: The Flagellation, University of Chicago Press 1972

- ‘The Piero Trail’, directed by Anna Benson Gyles, shown on BBC1 on 29th September 1992

- Gianmario Guidarelli, Gabriella Liva and Isabella Friso, ‘The “ideal” city and the “real” city painted by Tintoretto’, DisegnareCon Vol 11, No 21, 2018 pp.6.1-6.14