Venice, Venice, Venice, Venice, Venice...

In the late 19th century patients with respiratory diseases moved to parts of rural California now built over by Los Angeles for the sake of their health - surprising as it might seem today - to benefit from the pure air and sunshine. Abbot Kinney, an asthma sufferer, spent a night in 1880 at the Sierra Madre Villa Hotel and had the best night’s sleep of his life - even though he arrived without a reservation and had to sleep on the hotel’s billiard table. He decided to move to California and, with a fortune made in the tobacco business, embarked on a series of development projects, culminating in the foundation of a seaside resort which he named Venice Beach. This was an independent city until 1926, when it was absorbed into LA.

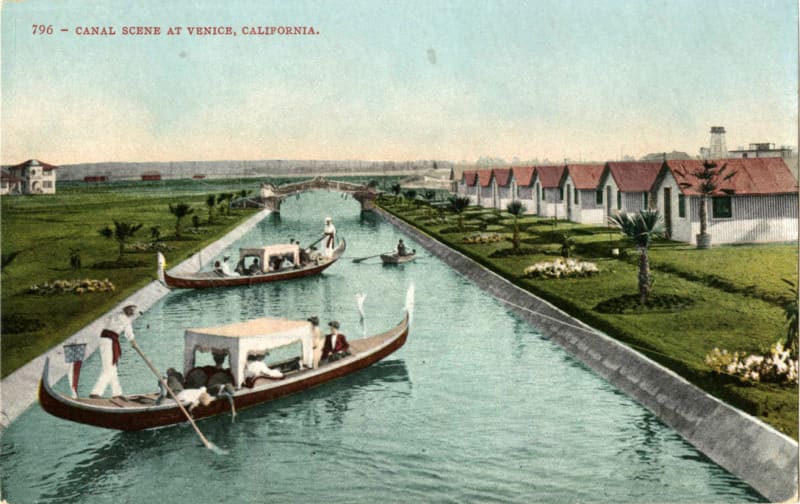

The town had an amusement park, beach entertainments, a pier, and a miniature railway. But the greatest attraction of Venice Beach was the resort’s reproduction, up to a point, of the beauties of its Italian namesake. Kinney had visited the real Venice on a walking tour of Italy. In California he arranged for a network of canals, converging on a central lagoon, to be dredged from saltwater marshlands. Pedestrian bridges were modelled loosely on their Italian prototypes, but made of concrete not masonry. There were commercial buildings with colonnades, evocative of Saint Mark’s Square. Visitors could travel by gondola, rowed by professionals brought from Italy. The houses on the other hand were mostly small Californian bungalows with gardens – despite a label on Kinney’s original plan mentioning ‘Venetian villas.’

In 1929 most of the canals were filled in and paved over to make streets. One reason was that the flow of water was insufficient, and the canals had become silted up and insalubrious. But the real impetus was the increase in car ownership, which grew earlier and faster in California than anywhere else in the United States. Previously Venice Beach had, like its model, been a pedestrian town, with access from Santa Monica and Downtown LA provided by the Red Cars of the Pacific Electric Railway. Today there are still a few stretches of waterway in the Venice Canal Historic District. But the long-time locals are being forced out by gentrification.

Venice Beach California was only the first – and for all its deficiencies perhaps the sincerest in spirit – of a whole series of re-buildings of Venice Italy as theme parks and leisure destinations in the 20th century. Disney World in Florida represents Italy with a tribute to Venice in the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT) opened in 1982. The Doge’s Palace, the Campanile and the freestanding marble columns of the real St Mark’s Square are all faithfully reproduced in authentic materials, although the Palace is cut down from the original in length and width. One can take trips in motor boats elsewhere in the resort. There are however no canals in the Italian district.

On the other hand the Venetian Resort Hotel in Las Vegas has a Grand Canal offering gondola rides with singing gondoliers, as at Venice Beach. The Doge’s Palace is impeccably reconstructed, this time at full size, as are the Campanile, the ‘famed Rialto Bridge’, and the arcaded buildings flanking St Mark’s Square. Their spatial relationships are however all shuffled. Where St Mark’s Basilica should be, there is a row of shops with a canal in front, flowing right into the Square. As for the interior reception spaces, the Hotel’s publicity assures us that “The frescos that adorn the resort’s ceilings were hand painted by famous Italian artists.”

At the opening ceremony in 1999, the chairman Sheldon G Adelson shared a motorised gondola with the Italian actress Sophia Loren. Most of the craft today however seem to be propelled in the traditional way. Gondola rides are $116 for two persons (in 2019). “On any day, the most-asked question to a gondolier at The Venetian is ‘How can I become a gondolier?’” The answer is to take an afternoon course at Gondolier University, from which each graduate receives a gondolier’s hat and T-shirt, a photo and a degree certificate.

The Venetian in Macau, opened in 2007, is an exact copy - with all the Venetian buildings - of its sister hotel in Las Vegas. It was built by the same company, and houses the largest casino in the world. Elsewhere in Asia the real Venice has inspired imitations that depart further from their model. At the Everland Resort in South Korea - one of the world’s biggest entertainment parks - we reach a nadir with a shrunken Doge’s Palace, a cut-down Campanile half the height of the original, and no canal in sight. Bianca Bosker in her book *Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China *shows pictures of Venice Water Town, Hanghzhou, where gondoliers navigate between rows of palazzo-like apartment blocks. The Doge’s Palace carries an illuminated sign in large Chinese characters above the cornice. This is not a paying attraction but a ‘real’ upmarket housing development.

Meanwhile back in Italy, has Venice itself become a theme park? In 2019 the resident population was down to some 54,000 while the number of tourists per year was estimated at between 26 and 30 million. Overcrowding has become so serious that temporary turnstiles have been installed on two of the main bridges across the Grand Canal to control the flow at peak times. In high season, rubbish bins have to be emptied every half hour. Gigantic cruise ships, towering above and overshadowing the buildings, pass through five or six times a day, trailing pollution and eroding the mudflats of the Lagoon. Their passengers descend only to visit the sights and go back to the ships to dine and sleep. The city has for some time levied a tax, via hotels, on those who stay the night: it now intends to impose a charge on day visitors of up to 10 euros per person, although exactly how this will be collected remains undecided. If one complains to Venetian residents that their city has become Disneyland, they will reply wearily ‘Magari!’ (‘If only!’)

[Ruth Brandon had the idea for this piece: I stole it from her. It was written before the pandemic, since when the prospects for tourism in Venice may well have changed. I am grateful to Phil Tabor, a resident of the city, for his help. Phil rowed with Gillian Crampton Smith (but not in a gondola) down the centre of the Grand Canal in May 2020, when theirs was the only boat moving.]

Bianca Bosker, Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China, University of Hawa’i Press, Honolulu/ Hong Kong University Press 2013