Canaletto and the Camera Obscura

In June 2025, UCL Press will publish my book Canaletto’s Camera (see the separate item under ‘Publications’). This is the fruit of a project supported by an Emeritus Fellowship from the Leverhulme Trust, awarded in 2021, for which I am immensely grateful.

Research for the book has involved working in three ways. I have analysed a sketchbook from the 1730s which Canaletto filled with 120 pages of drawings of Venetian buildings made with a camera obscura. I have compared Canaletto’s works with photographs taken specially from the pictures’ viewpoints in Venice by my colleague Gregorio Astengo. A second colleague Adam Azmy has reconstructed an 18th century design of camera obscura, which we have taken to places where Canaletto painted in London and have made sketches. I show how Canaletto had contacts with a circle of contemporary Venetian and Paduan scientists, in particular Giovanni Poleni, Antonio Conti, and Francesco Algarotti. All of them were enthusiastic about the theories of Isaac Newton, who describes the camera obscura in the opening pages of his great book on Opticks.

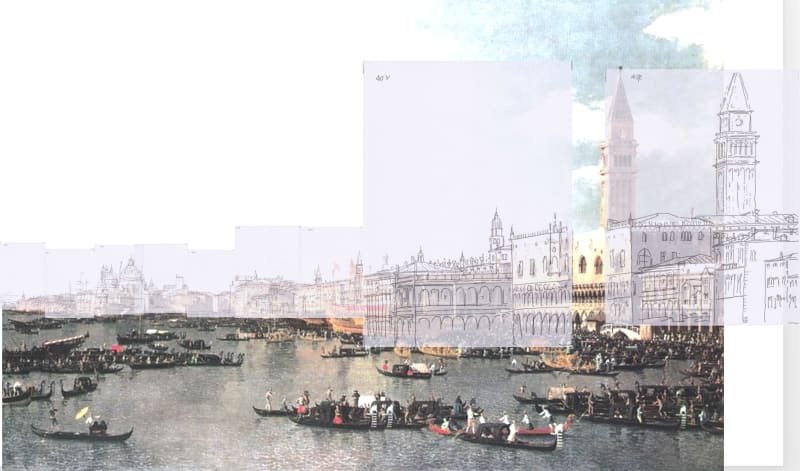

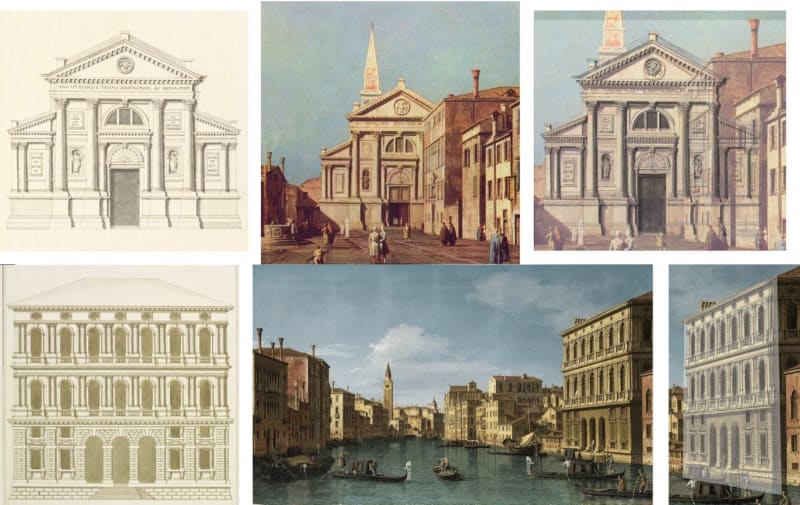

I propose that Canaletto used the camera for two purposes: tracing from real scenes; and copying and collaging drawings and engravings by other artists. In particular, Canaletto relies on a large number of measured drawings of Venetian buildings by his colleague Antonio Visentini. This debt to Visentini has not previously been recognised by historians. Canaletto used this raw material - his camera sketches and drawings by Visentini and other artists - to produce his paintings and finished drawings, manipulating the material in discreet ways in the realistic views, the vedute, and in more extreme ways in his fantasy pictures, the capricci. There is not so sharp a boundary between the two types of picture as has sometimes been thought. Using our camera, we have copied drawings, altered their scales, mirrored them, and turned frontal views into oblique perspectives. Through these tests, and the recreation of both a veduta and a capriccio using processes of ‘photomontage’, the book sheds new light on Canaletto’s artistic procedures. He was a ‘photographer’, a hundred years before the invention of chemical photography.

Below is a selection of illustrations from the book, and a more detailed account of how we used our camera on the roof of Lambeth Palace, a vantage point from which Canaletto made sketches for a panoramic view of the Thames in 1746.

Canaletto at Lambeth Palace

Canaletto painted this view of the Thames and the old Westminster Bridge from the roof of Lambeth Palace in 1746. The painting is one of two Canalettos now in the Lobkowicz Palace in Prague. It seems that the pictures were bought by Prince Lobkowicz directly from Canaletto on a visit to London.

As part of the project on Canaletto, Adam Azmy, craftsman and filmmaker, has reconstructed an eighteenth-century design of camera obscura published by the Dutch mathematician G J ‘s Gravesande in his Essai de Perspective of 1711. There are reasons to believe that Canaletto used an instrument of this general type for making sketches, which then served as the basis of finished drawings and paintings. Our camera takes the form of a tent which the artist sits inside. An optical image is projected by a tilted mirror, down through a lens in a vertical tube onto a table, where it can be traced. Azmy’s version reproduces the optics and dimensions of Gravesande’s design in modern materials.

In October 2022 we took the camera to Lambeth Palace with the kind permission of the Palace authorities. We installed it on the roof of Morton’s Tower, the painting’s viewpoint. I made tracings inside the camera. The photos show the view as it is today, and the camera in position, with my legs visible under the table. I am facing away from the subject.

The view is an extremely wide panorama, perhaps made with the camera pointed in three directions. The chapel and other buildings of the Palace are visible at the right-hand side of the painting. The chapel was bombed in World War 2, and the flat roof visible in the painting was replaced with a new pitched roof. St Paul’s Cathedral is visible at the extreme right but is hidden behind nearer buildings today. Westminster Abbey is seen at the left: today only its towers are visible behind the Houses of Parliament. Plane trees have grown up to obscure some of what Canaletto depicted. The picture can be dated to 1746 by the state of the new (old) Westminster Bridge, which is nearing completion, but has some sections of balustrade still to be added. The bridge was replaced in the nineteenth century.

The pictures below show the optical image on the drawing table inside the camera, and three pages of sketches made of the buildings of the Palace.

Aspects of the Canaletto work have been published in a book, Hockney’s Eye: The Art and Technology of Depiction, and in a paper in the Drawing Matter Journal. A paper by Gregorio Astengo and myself, ‘Canaletto’s use of drawings of Venetian buildings by Visentini’ will appear in The Burlington Magazine in 2025.