Renaissance Fun: The Machines Behind the Scenes

Contents

Introduction

Part I: The Machine in the Theatre

Chapter 1: Changing the scenes

Intermezzo: Moving pictures

Chapter 2: Theatres of machines

Intermezzo: Artificial weather

Chapter 3: The automata of Hero of Alexandria

Part II: The Machine in the Garden

Chapter 4: Artificial creatures

Intermezzo: Talking heads

Chapter 5: Water in the air

Intermezzo: Surprise soakings

Chapter 6: Artificial music

Part III: A Garden and and Opera

Chapter 7: The ‘garden of marvels’ at Pratolino

Chapter 8: Mercury and Mars in Parma, 1628

From the Introduction:

In November 1643 the diarist John Evelyn set out from England on a series of journeys around the Low Countries, France and Italy in an early version of the Grand Tour. He visited the classical ruins of Rome and southern Italy; and he saw many of the paintings, sculptures and works of architecture produced in the Renaissance of the visual arts of the previous two centuries.

But Evelyn also enjoyed a great variety of other entertainments and amusements, some serious and refined, others vulgar and trivial. In November 1644 he paid a visit to the Jesuit college in Rome, where the polymath Athanasius Kircher entertained him and his friends with ‘many singular courtesies’. For Evelyn’s party Kircher brought out, ‘with Dutch patience’, his ‘perpetual motions, Catoptrics, Magnetical experiments, Modells, and a thousand other crotchets & devises’.‘Catoptrics’ was the study of mirrors and the reflection of light. Kircher devised several optical entertainments making use of mirrors and lenses, including camera obscuras and magic lanterns.

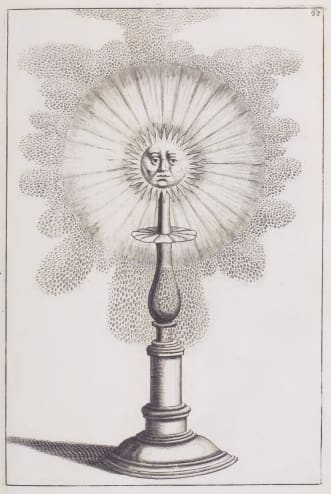

Evelyn visited many of the great Renaissance and Baroque gardens of Italy and France, and admired their walks, parterres, groves and statuary both ancient and modern. He was entranced by the ‘jettos’ of water that made patterns of spray in the air in the shapes of glasses, cups, crosses, crowns, and suns. Other fountains imitated the sound of thunder or produced artificial rainbows. In May 1645 he went to the gardens of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, where he enjoyed the scale model of the city of Rome with its stream representing the Tiber. He writes:

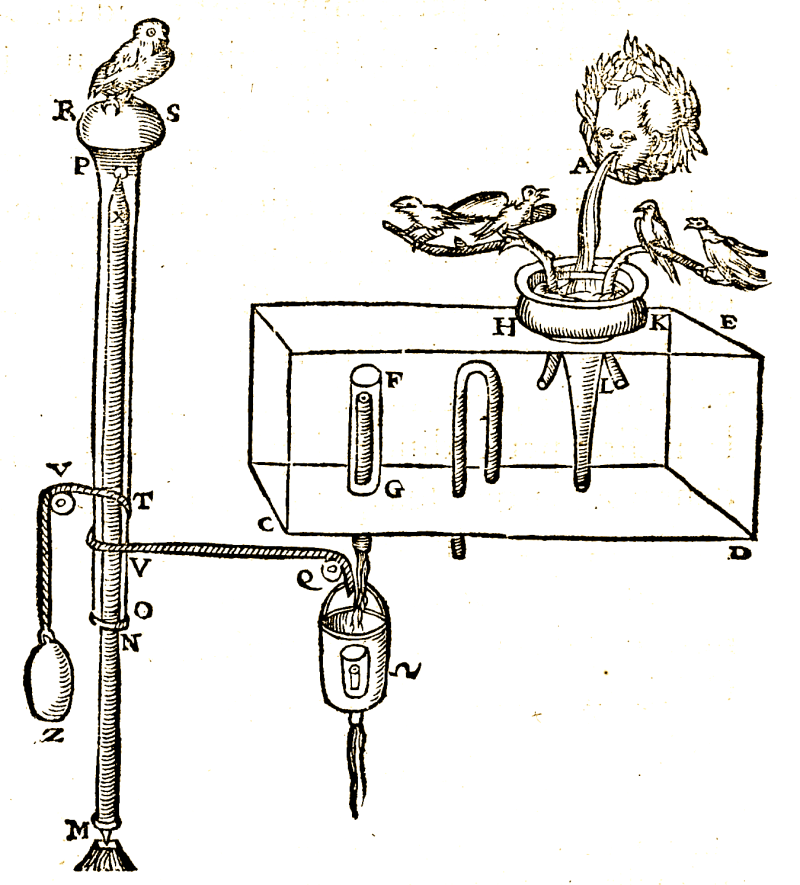

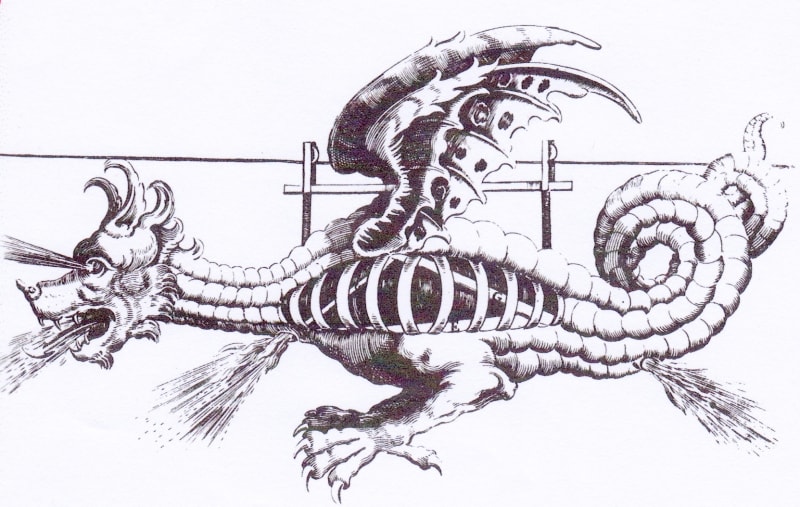

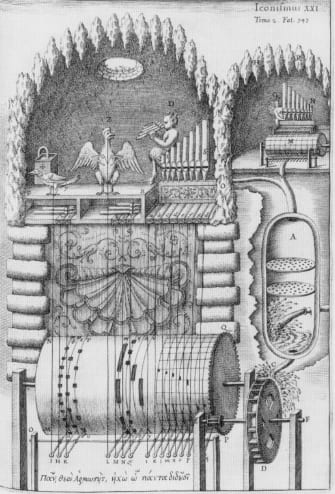

“In another garden a noble Aviarie, the birds artificial, & singing, til the presence of an Owle appeares, on which the[y] suddainly chang their notes, to the admiration of the Spectators: Neere this is the Fountaine of Dragons belching large streames of water, with horrid noises: In another Grotto, called the Grotta di Natura, is an hydraulic Organ …” This was not the only water-powered organ that Evelyn saw. He mentions hearing ‘artificial music’ in several places on his travels.

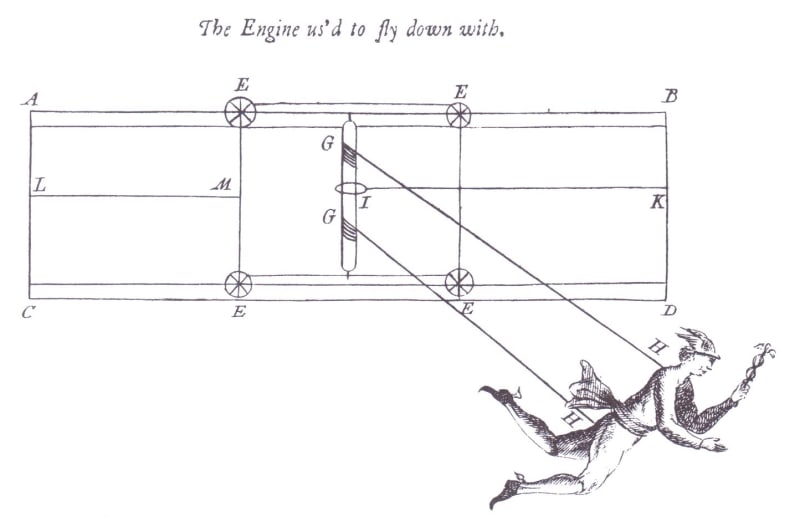

One more type of entertainment about which Evelyn was greatly enthusiastic was the theatre. Arriving in Venice in June 1645, he went to the opera accompanied by ‘my Lord Bruce’ to see a performance of Hercules in Lydia. The music and singing were ‘excellent’, ‘with variety of Seeanes painted & contrived with no lesse art of Perspective, and Machines, for flying in the aire, & other wonderfull motions. So taken together it is doubtlesse one of the most magnificent & expensfull diversions the Wit of Men can invent.’ In Hercules the scenes were changed 13 times.

The common factor in all this variety of entertainments was that they depended on machines. The fountains relied on elaborate systems of water control: aqueducts, reservoirs, pipes and nozzles. Animal and human automata were worked by concealed hydraulic, pneumatic and mechanical apparatus. The machinery of the Renaissance theatre brought celestial personages down from the clouds (‘gods from machines’) and brought characters from the Underworld up from below. Scenery was rotated, slid, rolled and replaced using yet more mechanical devices. Sets were built and painted to create realistic illusions of depth using the new methods of perspective.

How did these machines work? How exactly were chariots filled with singers let down onto the stage? How were flaming dragons made to fly across the sky? How were seas created on stage? How did mechanical birds imitate real birdsong? How could pipe organs be driven and made to play themselves automatically by waterpower alone?

Vitruvius and Hero

The designers of Renaissance entertainments looked back to the work of their predecessors in the ancient world. They studied such archaeological evidence as remained: the fountains, theatres and ruined villas of Rome and the Empire. Above all they read those few texts on machines that survived from Rome, Greece and Alexandria. These were translated into Latin and Italian and were studied intently by Renaissance engineers in an attempt to recover and recreate some of that lost world of knowledge and expertise.

First among these ancient writers was Vitruvius, a Roman military engineer and architect who lived in the first century BC. His book On Architecture covers the design of theatres and the scenic decoration of the ancient drama. Vitruvius also devotes just a few sentences to painting in perspective, and its use in the design of stage scenery.

The impact of Vitruvius’s writings on Renaissance theatre design from the fifteenth century was very great, and reached a high point in Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza of 1585. After this, however, Vitruvius’s influence waned, with a move in theatrical taste away from classical drama towards modern comedies and musical entertainments that demanded a very different kind of theatre building, with much more elaborate scenic machinery.

Interest among designers turned to a second ancient writer: Hero of Alexandria, who lived in the first century AD and worked in Alexandria, where he probably taught and studied in that city’s far-famed Museum and Library. His best-known work is the Pneumatics, which despite the title is largely devoted to ingenious and entertaining devices, some of which operated automatically. These provided models for the automaton figures of humans and animals that populated the garden grottoes of late Renaissance gardens.

Hero wrote another book, much less well known, On Automata-Making. This describes the construction of two miniature theatres that put on elaborate performances without human intervention. One of these had a proscenium arch with doors that opened onto a series of scenes, in which figures of men and gods moved in front of mobile scenery. It is thus quite unlike the classical open-air theatre; but it does bear close similarities to both the form and the workings of the new Italian theatres of the late sixteenth century. Hero’s importance for Baroque theatrical machinery – which has previously been little appreciated – was crucial.

Reviews

Steadman is not trained as an historian, and he acknowledges this without reservation. He is, however, a seasoned professional architect, with considerable archival research experience and a flair for writing in an engaging style, as he demonstrated in his 2001 book Vermeer’s Camera. This background enables him to delve deeply into the construction and operation of mechanical theatrical devices, table decorations and garden designs. He does this in a conversational and easily accessible style, utilising 196 eye-catching figures consisting of diagrams, photographs, engravings, and reproductions of manuscript pages. Overall, he realises his intention for the book itself to be a piece of entertainment.

Luciano Boschiero, Metascience

In Renaissance Fun Philip Steadman investigates the devices whereby the truly spectacular effects of the Renaissance and Baroque stage - including shipwrecks, storms and divine descents from heaven - were achieved. He also reveals the secrets of the moving statues and water organs of 16th-century gardens and displays of moving images projected in a camera obscura. This is a learned and pioneering study of a hitherto neglected subject, and also (as its title suggests) full of entertaining information.

Martin Gayford, Spectator Art Books of the Year

This is a beautifully engineered book, easy to read and full of interesting examples and detail.

Mary Ann Auckland, The Magic Lantern

I believe this new book to be useful to a wide range of students and scholars: Renaissance scholars of all sorts, historians of science and technology, art historians, theater historians (and practitioners), scholars working on festival culture, Italian historians, and early modern literary scholars. The book should also prove to be a wonderful aid for teaching.

Alison Calhoun, Early Science and Medicine

This book about Renaissance diversions was written primarily for the sake of entertainment, according to its author, and it is a joy to read indeed. Its ingenious composition, tailored to the book’s contents and argument, significantly contributes to this.

Joseph Wachelder, Technology and Culture

- A lecture at UCL on ‘A Renaissance theme park: the lost ‘garden of marvels’ at Pratolino’

- Renaissance Fun, UCL Press